Today, the good folk of the motor racing fraternity get a little green about the gills when the grey tendrils of politics are seen to encroach upon the virgin purity of their vocation. Mind you, trying to keep up with Damon Hill’s many back-flips over whether or not he believes a particular race should happen on political grounds would make anyone a touch queasy…

The fact remains, however, that in the days of Scarf & Goggles motor sport was quite simply an extension of foreign policy for most participating nations – be they hosts or participants. After all, once internal combustion had proven itself to be far superior to electricity, steam and any other form of motivation in the great races of the 1890s, there had to be a point to competition.

That point was granted by James Gordon Bennett Jr, the millionaire owner of the New York Herald. In 1899 Gordon Bennett inaugurated a trophy to be raced for annually by the automobile clubs of the various countries. Manufacturers would build cars that would be painted in the uniform colour of their nation: blue for France, white for Germany, red for Italy and green for Great Britain.

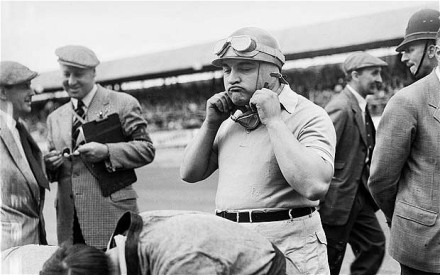

Racing for Britain: Napier shows off its green fleet of Gordon Bennett entries

The early 1900s were a time of fierce nationalism, sabre-rattling and military expansion which ultimately ended in World War 1. The whole of Europe was in a state of fervour, and motor racing provided a white hot crucible in which the technology of the arms race and the national status of the military powers could be trumpeted. Gordon Bennett was on to a winner from the outset.

The Gordon Bennett races were succeeded in 1906 by Grand Prix racing, but the nationalistic fervour which surrounded these races was no different – nor indeed were the racing colours. While the 1914 Grand Prix contest between the vast, organised might of Mercedes and the quixotic local hero Georges Boillot’s Peugeot was certainly spectacular in itself, it was undoubtedly given piquancy to the hundreds of thousands of French fans in the wake of the assassination of Archduke Franz-Ferdinand and the mustering of arms that would soon be locked in battle.

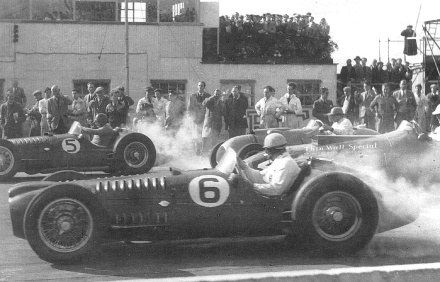

Boillot (5) and the Peugeot team carry French hopes into battle in 1914

After World War 1 motor racing had a short break from political life but it bounced back with a vengeance with the rise to power of Benito Mussolini. Il Duce wanted more than just the trains to run on time, he wanted to rebuild the Roman empire and to do that would mean making the whole of the Mediterranean aware that their neighbours could take on and beat the world in matters of might and technology.

Mussolini’s patronage of, and benefits from, the great racing programme at Alfa Romeo were a match made in heaven, in his view. The scarlet cars from Portello would howl their way to victory in Grand Prix and sports car races across the whole of Europe, only to be greeted by a beatifically smiling Duce upon their return home.

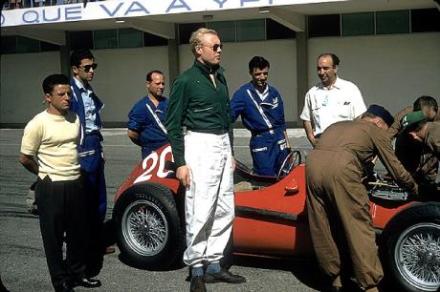

Mussolini in the hotseat to greet Tazio Nuvolari (centre) and the Alfa team

While Italy triumphed, a certain Austrian politician was busy making all sorts of promises about funding racing cars if he was to get into power in Germany. Adolf Hitler was wooed by the motor manufacturers and wooed them back in return, forming a triumvirate with Deutsche Bank that effectively created the mechanical power of the regime and sold it to the masses via motor racing.

Millions of Reichmarks were poured in to the racing funds of Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union by Hitler’s chancellery through the era of the ‘silver arrows’. The formidable German technology on show not only chewed up and spat out the competition across Europe, Africa and North America but also bred technology that was soon to be put to work in the latest weapons of war.

Ernst von Delius prepares for the 1937 Vanderbilt Cup in New York

But it wasn’t only Grand Prix racing. Motorcycle racing and sports cars were equally important to the NSKK (Nationalsozialistische Kraftfahrkorps, responsible for all automotive matters in the Reich) as the means to show German supremacy.

As for the races themselves, Germany and Italy turned their major race meetings into idealogical pageants, with flags a-flutter and uniformed stormtroops aplenty… the crowds at the Nürburgring were also treated to such pre-race entertainment as a display by the prototype Stuka dive-bomber.

BMW ace Huschke von Hanstein made his sponsorship clear

Both the German and Italian teams also had to be selective in their driver line-ups. For the German teams in particular, hiring non-German drivers was only ever done in line with national priorities. Occasionally the teams were then ‘requested’ by NSKK officials to deploy team orders, such as when Auto Union was required to allow Hans Stuck to surrender certain victory in the 1935 Tripoli Grand Prix to his Italian team-mate Achille Varzi.

You might be forgiven for thinking that, in the wake of World War 2, such political engineering would be consigned to history – but such was not the case. The cars retained their national racing colours, and when Tony Vandervell set out to create his world championship-winning Vanwall team in the mid-1950s, he did so with the sole objective of beating ‘those bloody red cars’.

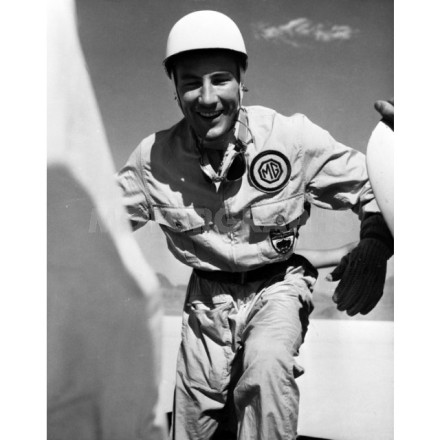

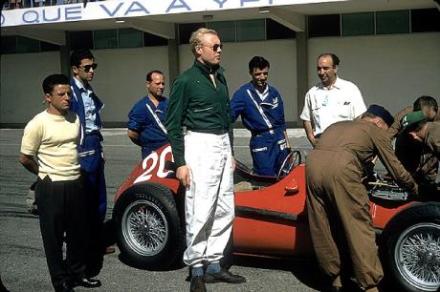

Flying the flag: Hawthorn keeps a corner of Maranello forever England

Among the drivers, too, there was strong feeling. Stirling Moss always wished for a competitive British car, and when none was available made certain that his mount would at least carry British colours. Mike Hawthorn raced a green Ferrari in his first races of 1953 as a tribute from Enzo Ferrari himself, and later added a green windcheater to his racing uniform to ensure that, even when the cars were red, a flash of green was on show.

Of course Stirling also benefited from the pre-war ethos of team orders when at Mercedes-Benz, being handed his victory at Aintree in 1955 by his team-mate Fangio as a handy bit of PR for the Stuttgart marque.

Moss beats Fangio at Aintree – to Mercedes’ great relief

Today the modern version of Grand Prix racing takes the sport to nations which pay for the spectacle from public funds and seek to gain something back in terms of status, tourism, business and PR. The Caterham team, meanwhile, is owned by 1Malaysia, a government organization intended to promote racial harmony among its discordant Chinese, Indian and Malay population.

So it’s clear that, today, the sport is still carrying on at least some of the traditions that have kept it in rude health for more than a century. Politics are part of the fabric of life in all walks – although motor sport still has a long way to go to catch up with the Olympics!