Welcome to 2018 and to the continuation of this little series of features on British achievements on two, three and four wheels. Or more. It’s not definitive by any stretch, but intended to prod the collective consciousness of what British engineers, teams, drivers and riders could do on their day – and may yet continue to.

As per Martin Field’s request, it is de-Schama’d and written in the past tense. For some reason this makes it rather harder to write – so there’s a secret of Simon Schama’s success revealed for you right there.

How much further this record will go on is not yet clear. The cut-off of the S&G is 1961 but perhaps for the sake of context we’ll go onwards, although the last 20 years makes for pretty depressing reading all things considered. Still, on we go into that period when British engineering was at its pinnacle, fuelled by the necessity of war and honed through the absence of funding or raw materials in the age of austerity that came with peace. Let’s have a little look-see, shall we?

1945:

- British intelligence worker Cameron Earl investigated the pre-war German Grand Prix teams to mine them and their staff for information to help establish British supremacy in international motor racing. His findings were published in 1946 and used as a guide by many aspiring British designers.

- The British Racing Drivers’ Club (BRDC) established a fund to support renovation of the circuit and facilities at Le Mans damaged by Allied bombing in WW2.

- English Racing Automobiles (ERA) evolved into British Racing Motors (BRM), revealing plans to build a supercharged 1.5-litre V16 car and run it along the lines of the great pre-war German teams.

1946:

- The 500 Club was formed for 500cc motorcycle-engined racing cars, eventually becoming known as Formula 3.

- Hersham and Walton Motors (HWM) became a racing car constructor with George Abecassis and John Heath building a sports car on the foundations of a pre-war Alta.

- Val des Terres hillclimb in Guernsey held its first event.

- The wartime Boreham Airfield in Essex became racing venue.

- Jaguar revealed the all-alloy XK120 road car, with very obvious potential for turning it into a potent racing car.

1947:

- The former RAF training airfield at Silverstone was selected as the new permanent home of British motor racing by the BRDC and RAC.

- What remained of Aston Martin, which had been turned over to manufacturing aircraft components in World War 2, was bought by tractor manufacturer David Brown.

- John Cobb raised the Land Speed Record to 394.196 mph in his pre-war Railton Special, with funding from Mobil. This record stands as the fastest achieved by an internal combustion engine and wheel-driven car.

- Harold Daniell won the Senior TT on its first running after World War 2, riding a Norton. Bob Foster won the Junior race for Velocette.

- Fergus Anderson won the first European Motorcycle Championship title for Britain after the war, taking 350cc honours for Velocette.

- Stirling Moss won the Junior Car Club Rally in a BMW 328.

- The Brooklands Automobile Racing Club and the Junior Car Club amalgamated as the British Automobile Racing Club (BARC). The new body relocated to new headquarters at the former RAF Westhampnett airfield on the grounds of the Duke of Richmond & Gordon’s estate at Goodwood.

- The Darlington & District Motor Club started holding races on sections of RAF Croft airfield.

- Former Napier racing engineer and Brooklands regular Charles Cooper, together with his son John, who worked on special engineering projects such as mini-submarines in WW2, formed the Cooper Car Company in Surbiton, after building a series of lightweight rear-engined racing cars using 500cc JAP motorcycle engines and Fiat Topolino sub-frames.

In 1952 the Coopers revealed a streamlined car styled after the pre-war Auto Unions

1948:

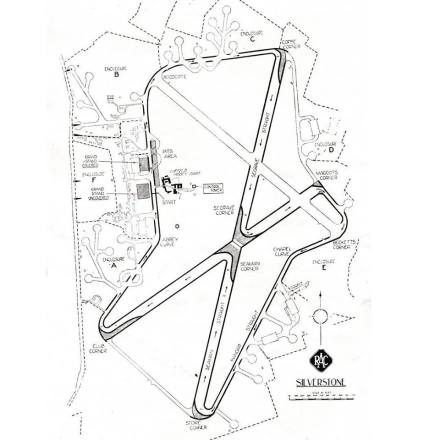

- Silverstone hosted its first RAC Grand Prix to the newly-renamed Formula 1 regulations for 4.5-litre unsupercharged or 1.5-litre supercharged cars, organised by Colonel Barnes and Jimmy Brown. The circuit layout saw the perimeter track and runways in use, the cars turning infield at Copse up to a sharp hairpin before re-joining the perimeter at Maggots, then turning infield at Stowe and charging up the runway before another tight hairpin pointed them back towards Club. The race was won by Luigi Villoresi in a works-supported Maserati, with team mate Alberto Ascari 14 seconds behind. Bob Gerard’s ERA came third.

- Ian Appleyard and Dick Weatherhead won the Rallye des Alpes in an SS100 Jaguar.

- Artie Bell won the Senior TT for Norton, Freddie Frith winning the Junior TT.

- Freddie Frith won the 350cc European Motorcycle Championship for Velocette while another British rider, Maurice Cann, won the 250cc title for Italian manufacturer Moto Guzzi.

- Goodwood Circuit opened with its first meeting organised by the BARC.

The first Silverstone grand prix layout

1949:

- Silverstone hosted its second Formula 1 race on a revised circuit using only the perimeter road except a chicane running on to the runway at Club corner. It was the first British Grand Prix, so named after the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) granted the RAC’s race Grande Épreuve status: equal with that of the French and Italian races as the most prestigious events of their kind. It was won by Baron ‘Toulo’ de Graffenried in a Maserati. Raymond Mays demonstrated the BRM V16, built and operated along the guidelines from Cameron Earl’s study of the pre-war German teams.

- Goodwood hosted its first Formula 1 race, the Glover Trophy, won by Reg Parnell in a Maserati.

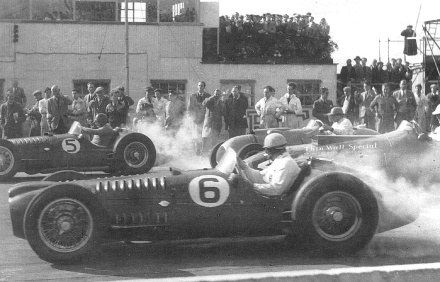

- British industrialist Tony Vandervell, producer of ‘thin wall’ bearings and an early investor in BRM, began to grow wary of the ambitious V16 project’s potential and negotiated with one of his customers, Enzo Ferrari, for the purchase of one of the Italian’s Formula 1 racing cars. The car was painted green and renamed the ‘Thin Wall Special’ for use in Formula Libre races and occasional grand prix outings.

- Britain’s Board of Trade unsuccessfully attempted to block the import of foreign racing cars. Tony Vandervell argued that a supercharged Ferrari was required as a development mule for improved engine bearings for the British motor industry. A compromise suggested by the BoT was that the car should only be in the country for a maximum of 12 months and only used for testing work rather than competition. Vandervell then offered the customs duty and tax that was levied on the car’s purchase price for the government to shut up and go away – which worked! It also set a precedent that ensured very few aspiring racers could afford to import their cars and would have to rely on home-built machinery.

- Motorcycle racing commenced at Mallory Park.

- Lord Selsdon entered a Ferrari 166 MM into the Le Mans 24 Hours, which claimed victory having been driven for almost the entire duration of the race by Luigi Chinetti. An HRG won the 1.5-litre class driven by Eric Thompson and Jack Fairman.

- Ken Wharton and Joy Cooke won the Tulip Rally in a Ford Anglia.

- Donald Healey and Ian Appleyard won the 3000cc class of the Rallye des Alpes in a Healey Silverstone. Betty Haig won the Coupe des Dames in an MG TC.

- Harold Daniell became the first rider to win Isle of Man TT races before and after the war, claiming the Senior TT event for Norton, while the Junior TT fell to Freddie Frith for the second year running.

- Les Graham won the inaugural 500cc World Motorcycle Championship for AJS, while Freddie Frith won the inaugural 350cc World Motorcycle Championship with five wins in five races with Velocette. Ian Oliver and Denis Jenkinson claimed the Sidecar title for Norton.

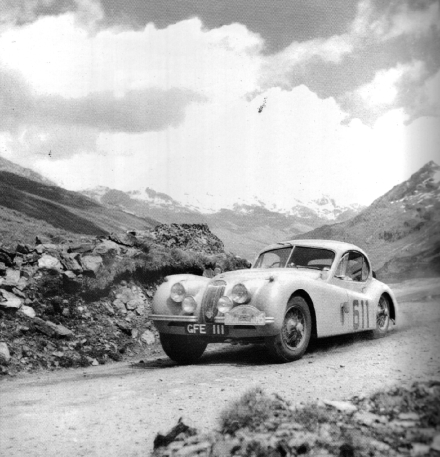

The Jaguar XK120 won rallies and races with alacrity

1950:

- Silverstone hosted the 11th Grand Prix d’Europe, the first ever points-scoring round of the FIA Formula 1 World Championship. The occasion was attended by HRH King George VI, Queen Elizabeth and the two royal princesses with all pomp and the band of the grenadier guards in attendance. The race was won by Dr. Giuseppe Farina’s Alfa Romeo.

- BRM made long-overdue debut at Silverstone, although the mighty V16 cars did not shine. Only one car was in a fit state to take the start, driven by Raymond Sommer, but it shattered a driveshaft on the startline and pennies were thrown by the booing crowd as it was wheeled off.

- Autosport magazine was founded by Gregor Grant and John Bolster, supplementing the monthly output of Motor Sport.

- Ian and Pat Appleyard won the Rallye des Alpes in their Jaguar XK120.

- Stirling Moss won the Daily Express 1,000-Mile Rally of Great Britain in an Aston Martin DB2.

- Sydney Allard won the 8-litre class and finished third overall at the Le Mans 24 Hours, sharing the car with American driver Tom Cole. Aston Martin finished first and second in the 3-litre class, with the Jowett Jupiter of Tommy Wisdom and Tommy Wise beating the MG TC of George Philipps and Eric Winterottom to the 1.5-litre class.

- HWM built a new Formula 2 car with the pre-war Alta engine, performing well.

- After strenuous lobbying, Brands Hatch owner Joe Francis was convinced to lay a permanent asphalt surface at Brands Hatch for 500cc motor racing.

- The second Glover Trophy race for Formula 1 cars at Goodwood was won by Reg Parnell again, in his Maserati.

- Motor racing spread westward when motorcycle racing began on the runways of Thruxton airfield and on the perimeter road of RAF Castle Combe.

- Jaguar revealed a highly-evolved racing model of its celebrated sports car, the XK120-C, better known as the ‘C-Type’.

- Rising 500cc racing star Stirling Moss announced his presence on the international stage with a sensational drive to victory in the revived RAC Tourist Trophy at Dundrod in a Jaguar XK120.

- Newly-promoted Clubman rider Geoff Duke stunned the motorcycling establishment by winning the Isle of Man TT Senior race for Norton using the new ‘Featherbed’ frame.

- Ken Wharton won the Tulip Rally in a Ford V8 Pilot, with J. Graham Reece winning Class 2 in a Ford Anglia and Joy Cooke claiming the Coupe des Dames in another Ford V8 Pilot. Wharton also won the Lisbon International Rally.

- Italian manufacturers dominated most classes of the World Motorcycle Championship but Bob Foster maintained Velocette’s unbroken run in the 350cc class, while Ian Oliver retained the Sidecar title for Norton with Italy’s Lorenzo Dobelli alongside him.

1951:

- Silverstone hosted the third British Grand Prix, ending with Scuderia Ferrari’s first world championship Formula 1 win, taken by Argentine driver José Froilán Gonzáles in a Ferrari 375. The BRM finished fifth.

- Jaguar won the Le Mans 24 Hours, with Peter Walker and Peter Whitehead sharing a Jaguar C-Type. They became the first British drivers in a British car to win since Johnny Hindmarsh and Luis Fontès in their Lagonda in 1935. In a brilliant weekend for Britain, Aston Martin won the 3-litre class and a Jowett Jupiter took the 1.5-litre class win.

- Stirling Moss won his second RAC Tourist Trophy, this time at the wheel of a works Jaguar C-Type.

- Ian and Pat Appleyard won the Tulip Rally in their Jaguar XK120.

- The RAC Rally was revived as a 1000-mile run to Bournemouth from various starting points across the UK. An award for ‘Best Performance’ was made rather than declaring a win, and it was handed to Ian and Pat Appleyard in their Jaguar XK120.

- Geoff Duke and Norton dominated the World Motorcycle Championship, claiming both the 350cc and 500cc titles, winning both the Senior and Junior TT on the way. Ian Oliver won his third straight Sidecar world championship for Norton, with Lorenzo Dobelli riding beside him.

- Frazer Nash became the first British manufacturer to win the Targa Florio, with a car driven by Franco Cortese.

- Aston Martin employed pre-war Auto Union technical chief Robert Eberan von Eberhorst to redesign its sports cars, resulting in the DB3.

Jaguar won its first Le Mans 24 Hours in 1951, 16 years after the last British triumph

1952:

- The BRDC took over the lease of Silverstone Circuit.

- Goodwood became the first circuit in Britain to race at night, like Le Mans, with the inaugural Nine Hour race for sports cars. Floodlights were put in place to illuminate the grandstands and pits, the kerbs were given a coat of luminous paint, a beer tent was erected (although due to post-war licensing laws it had to stop serving before the race ended) and sponsorship came from theNews of the World. The event was not well attended by the public, for whom nine hours was simply too long, but it was won by Aston Martin’s works team after the Jaguars faltered.

- Lotus cars was founded by engineers Colin Chapman, Colin Dare and investors Michael and Nigel Allen, opening a factory in Hornsey, North London.

- Sydney Allard won the Monte Carlo Rally in his self-built car, with Stirling Moss finishing second in a Sunbeam shared with Desmond Scannell and John Cooper.

- Leslie Johnson and Tommy Wisdom won the 5-litre class and finished third overall at Le Mans in a Nash-Healey in the Le Mans 24 Hours, with a Jowett Jupiter again winning the 1.5-litre class.

- Godfrey Imhof and Betty Frayling won the RAC Rally in a Cadillac-powered Allard.

- Ken Wharton won the Tulip Rally in a Ford Consul.

- John Cobb was killed attempting to beat the Water Speed Record on Loch Ness in his jet-powered boat Crusader.

- Maurice Gatsonides won the Alpine Rally overall in a Jaguar XK120, with George Murray Frame winning the up-to-3-litre class in a Sunbeam.

- P. Denham-Cookes won the Scottish Rally in a Jaguar XK120.

- The British Grand Prix at Silverstone was won by Alberto Ascari in his first dominant world championship season to Formula 2 regulations, driving a works Ferrari 500 F2. He finished a lap clear of team mate Piero Taruffi, who was a further lap clear of Mike Hawthorn’s Cooper-Bristol in third.

- A Jaguar XK120 won the Liège-Rome-Liège Marathon de la Route in the hands of Jean Heurtaux and Marceau Crespin

- Former spy Cameron Earl died after crashing ERA R14B on a test run at the Motor Industry Research Association track (MIRA) in Warwickshire.

- HWM closed its Formula 2 team.

- Scuderia Ferrari attended the Easter meeting at Goodwood, where British youngster Mike Hawthorn challenged the mighty Italians in a home-prepared Cooper.

- Stirling Moss made his Grand Prix debut.

- Charterhall Circuit opened on another ex-RAF airfield in Berwickshire.

- Geoff Duke was beaten to the 500cc motorcycle world championship but retained honours for Norton in the 350cc category, while Cyril Smith triumphed for Norton in the sidecar class, joined by both Bob Clements and Les Nutt in the sidecar on points-scoring rounds.

1953:

- Maurice Gatsonides and Peter Worledge won the Monte Carlo Rally in a Ford Zephyr.

- Scuderia Ferrari signed Mike Hawthorn to drive for the team in Formula 1 and sports car races. At his first Grand Prix for the team, in Argentina, the Englishman was honoured with a bright green paint job. In arguably his greatest race, Hawthorn beat Juan Manuel Fangio in ‘the race of the century’: the fraught French Grand Prix at Reims, in which they passed one another several times per lap all the way to the flag.

- Aston Martin won the second Goodwood Nine Hours. Without the same level of off-track excitement as could be found at Le Mans, the News of the World had abandoned its sponsorship and it was sparsely attended.

- Petrol rationing ended in Europe and branded fuels went on sale again, leading to massive investment in motor racing. Shell launched its first ‘premium’ fuel since 1939, promoting it through racing success with Scuderia Ferrari.

- Duncan Hamilton and Tony Rolt won the Le Mans 24 Hours in their Jaguar C-Type, despite having been excluded after qualifying and retiring to an estaminet to drown their sorrows. Ken Wharton and Laurence Mitchell took honours in the 2-litre class in a Frazer Nash. Le Mans was a points-scoring round of the inaugural FIA World Sportscar Championship.

- Alberto Ascari won the second and final British Grand Prix held to Formula 2 regulations at Silverstone Circuit. Ascari’s works Ferrari 500 F2 finished a minute clear of Juan Manuel Fangio’s works Maserati, while Mike Hawthorn’s challenge was blunted by a gigantic spin and other issues that dropped him three laps behind.

- Ian and Pat Appleyard won the RAC Rally in their Jaguar XK120. George Hartwell and F.W. Scott won the Touring car class up to 2.6 litres in a Sunbeam-Talbot and Denis Scott the over 2.6-litre class in a Jaguar Mk.VII.

- A Jowett Javelin won the Tulip Rally in the hands of Count Hugo van Zulyen.

- D. Airth and R. M. Collinge won the ‘less than £800’ class in the Coronation Safari Rally in a Standard Vanguard.

- An Allard won the third 1000 Lakes Rally in Finland in the hands of Vilho Hietanen and Olov Hixen

- A Jaguar XK120 won the Acropolis Rally in the hands of Nick Papamichael and S. Dimitrakos.

- After a year off in 1952, the RAC Tourist Trophy counted as a points-scoring round of the inaugural FIA World Sportscar Championship. It was held at Dundrod once again and won by Peter Collins and Pat Griffith in an Aston Martin.

- Former 8th Air Force bomber airfield Snetterton in Norfolk became a licenced circuit

- Oulton Park circuit was formally paved and opened.

- Crystal Palace circuit reopened for motor racing after wartime bomb damage and other wartime materiel was finally cleared away, allowing a 1.39-mile layout to be used.

- The Monaco Grand Prix was staged as a sports car race as the Automobile Club de Monaco had no interest in holding a Formula 2 event. The race was won by Stirling Moss in a Jaguar C-Type.

- British riders reigned supreme in world championship motorcycle racing – but they rode for foreign manufacturers. Geoff Duke won the 500cc title on a Gilera and Fergus Anderson won the 350cc title for Moto Guzzi. Eric Oliver won his fourth sidecar title for Norton, with Stanley Dibben alongside him.

Ferrari’s young British star Mike Hawthorn at the 1953 British GP

![tf1[1]](https://scarfandgoggles.files.wordpress.com/2017/06/tf11.jpg?w=440)

The Scarf and Goggles bar at the 2015 Silverstone Classic

The Scarf and Goggles bar at the 2015 Silverstone Classic