It’s all getting rather fast and furious in the run-up to the referendum on whether Britain should remain in the European Union. Furious being the operative word for both sides in the debate. Fast being the operative word for how each side is playing with history.

Fast and loose.

It is not the place of the S&G to report or comment upon current political issues. It is, however, a place where history is cherished in the hope that it might continue to sparkle and inspire.

Not, it must be admitted, big History with a capital ‘haitch’ that discusses kings and queens, Spinning Jennies or the Cold War. The S&G commemorates sport, transport and adventure in the first half of the Twentieth Century (and only as much of that as time permits). But it is history nonetheless.

And right now history, great and small, is being trampled into the mud.

History is taking a beating from both sides in Britain’s debate on Europe

As an example of where all this is taking us, one imagines that Boris Johnson rather startled himself with the vehement response to his suggestion that the modern European superstate envisaged by the grey men of Brussels was essentially what Hitler had in mind. But that was an idiotic thing to have said.

If Boris had a clue about these things, he would in fact have suggested that in fact the way that the EU is heading mirrors the German justification for World War 1. It may deliver fewer headlines than a spectral swastika but infinitely greater resonance.

In 1913, Germany was the powerhouse of the European economy. She generated double the electricity of any other European nation; she produced two thirds of all European steel and was the centre of excellence as far as scientific advances went – from pharmaceutical and chemical research to automotive and aeronautical design.

All these wonders of the modern age were well and good but they needed to drive income and fuel the economy. Thus it was that, when Germany launched all-out war between the nation states of Europe in the summer of 1914, she very quickly followed up with the September Programme.

This was a draft treaty prepared by the German chancellor, Theobald von Bethman Hollweg, in anticipation of a swift military victory to the west.

Architect of ‘Mitteleuropa’: Chancellor Bethman Hollweg

Hollweg’s vision was of ‘Mitteleuropa’ – a free trade zone stretching between the Russian border and the English Channel and from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean. This ‘superstate’ would allow German products and technologies to be sold across national borders with no tariffs. Sounds familiar?

In effect, the September Programme stands as the only justification offered by Germany to explain the First World War: free trade for her products across Europe.

By taking control of Poland and Holland, Scandinavia would be brought into line by the sound of sabres rattling across the Baltic. Taking Belgium, Luxembourg and the disputed territories to the west would force the French government to acquiesce. It was brutal but elegant and would have avoided all the red tape for which Brussels is so renowned.

In this way, Hollweg believed that Mitteleuropa would be delivered and Germany would command all of Europe through her economic power backed up by her military achievements. Not only that but the dominions of the other European nations across Africa and the Far East would fall under German influence and thus bring her a wealth of resources like oil from the Dutch East Indies.

Having thus added an empire of her own to the free trade wonderland of Mitteleuropa, there could be little doubt that ultimately Germany would have had to go toe-to-toe with her island cousin, Great Britain. That is why she was building ships and u-boats as fast and as well as she could: to challenge the mighty Royal Navy of which Kaiser Wilhelm was so enamoured.

The battlecruisers let fly at Jutland

As we commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Jutland, there is a very clear measure of how advanced German industry was by contrast with that of Britain.

The three prime British ships lost in the engagement – Indefatigable, Queen Mary and Black Prince – were struck once, at the most twice, before blowing up. By contrast the Germans lost only one great ship – the Lǜtzow – which survived 24 direct hits before she was scuttled by her own crew, lest she be captured.

Wise cracks about German engineering are well-founded.

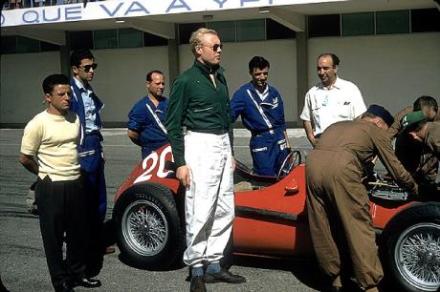

The triumphs of German engineering are legion

If Boris Johnson had invoked Hollweg instead of Hitler it would have won him fewer headlines but done him more credit – although it is not only the ‘Leavers’ who are using bad history to discuss the EU.

For one thing, David Cameron did what he presumably thought was a good impression of Aragorn at the battle of Pelennor Fields by suggesting that those lost in the wars of the last century would choose to be bound within Europe. He summoned up the dead of D-Day and the Somme – a fairly unforgivable presumption.

In 2010 the S&G was in Malta and staying in a hotel full of veterans of the great siege of 1940-42. The general election was coming up and politics dominated the conversation at breakfast time – a subject upon which most of the veterans felt completely alienated from all except the British National Party.

Then we are repeatedly told by the ‘Remainers’ that the single greatest Toby Jug on the mantelpiece of the British psyche, none other than Sir Winston Churchill, was one of the architects of the modern European Union.

Churchill, they cry, would therefore be campaigning to remain within the legal and political union.

Poppycock.

It is true that Churchill campaigned for a ‘United States of Europe’ in the years after World War 2 – but not for one second did he include the ‘Island race’ within such parameters.

“What I meant was…”

Speaking in Switzerland on 19 September 1946, Churchill sought to use the devastation wrought over the previous six years to galvanise the continent to action. His greatest desire was for the European nations to act swiftly to ensure that Germany was never allowed to repeat the aggression of 1914 or 1939 – by disassembling Bismark’s handiwork if needs be.

“The ancient states and principalities of Germany, freely joined together for mutual convenience in a federal system, might each take their individual place among the United States of Europe,” he said. Imagine that: an EU including Bavaria, Prussia, Swabia and 13 other states as sovereign nations.

‘Divide and conquer’ is another way of putting it. That was Churchill’s reasoning behind the proposal of a United States of Europe. Allowing German brilliance to enrich the continent for the common good, rather than mustering all her strength to bully and intimidate.

“I believe that the larger synthesis will only survive if it is founded upon coherent natural groupings,” he insisted.

“There is already a natural grouping in the Western Hemisphere. We British have our own Commonwealth of Nations. These do not weaken, on the contrary they strengthen, the world organisation. They are in fact its main support.”

And there you have it. Churchill was a supporter of a federal Europe: yes. A friend to a federal Europe: undoubtedly. But handing British sovereignty over to a federal Europe? Not on your nelly. Indeed, the old warhorse concluded:

“Great Britain, the British Commonwealth of Nations, mighty America, and I trust Soviet Russia – for then indeed all would be well – must be the friends and sponsors of the new Europe and must champion its right to live and shine.”

Eurovision: best left to the politicians

Let the arguments over British membership of the European Union continue but let them do so while being mindful of history. History either is or it is not. Sadly for politicians the world over, what it can never be is convenient.