It is undoubted that wealth and privilege could get you a long way in the age of adventure – but not without talent. One man who enjoyed more talent and privilege than most was Whitney Willard Straight.

Whitney Straight flies the mighty Duesenberg at Brooklands in 1934

Born in New York in 1912, Straight’s mother Dorothy was the beautiful heiress of prominent American politician and banker William Collins Whitney; a man who was credited with founding the modern US Navy in the 1880s.

His father, Willard Dickerman Straight, was an aspiring politician and financier who also involved himself in journalism and publishing – launching The New Republic magazine in 1914. This glamorous young couple married in Switzerland and moved to Beijing until Dorothy became pregnant with Whitney, having two more children – Beatrice and Michael – two years apart.

During the early years of World War 1, Willard Straight did considerable campaigning in America to support Britain and France against Germany. When the United States finally entered the conflict in 1917, Straight joined up and became a pivotal member of the US staff but succumbed to the Spanish Influenza epidemic of 1918 on the eve of the peace negotiations, leaving Dorothy to carry on philanthropic work in his name.

In 1920, Dorothy met and fell in love with Leonard Knight Elmhirst, an Englishman studying at the Cornell University. The university was one of the major causes of her and Willard’s life, and after Elmhirst had completed his studies and carried out philanthropic missions in India, Africa, Southern Asia and South America, he and Dorothy were married in 1925.

Dartington Hall, where Whitney Straight arrived age 13

The couple moved to England, together with the three children, where they settled upon Dartington Hall in Devon as a new family home. While his mother and stepfather involved themselves in plans to revive traditional rural life among the population, young Whitney developed an abiding passion for speed and mechanization.

By the time he was 16 (long before he was allowed to hold a licence), Straight had accumulated 60 hours of flying time. He duly went up to Trinity College at Cambridge where, in 1931, he decided to become an international racing racing driver. It was clear that there was talent which he demonstrated at the wheel of a Brooklands Riley – often piloting his own aircraft to different events while keeping a weather-eye on his studies!

It was not long before Straight met a kindred spirit at Trinity – a younger student called Dick Seaman, who was being groomed for a life in the diplomatic corps but who, like Straight, also wanted to be a racing driver. Straight encouraged Seaman to follow his passions – which he did, but only after convincing his parents that a Bugatti Type 35 was the ideal student runabout!

Straight’s contemporaries: Dick Seaman, Prince Bira of Siam and Count Felice Trossi

Straight, meanwhile, spent the 1933 season attacking a full schedule of both national and international events with his supercharged MG Magnette and a 2.5-litre Maserati that he bought from Sir Henry Birkin. Star performances took him to victory in the Brooklands mountain championship, Mont Ventoux Hillclimb, Brighton Speed Trials and the Coppa Acerbo Junior, putting the precocious American firmly on the map.

His talent and speed were evident and Straight himself even felt confident that he could take on the Maestro, Tazio Nuvolari, without fear – particularly if it was raining. Such was his confidence at the end of the 1933 season that Straight decided to drop out of Cambridge altogether and set about building a team with operations in Italy and Britain.

Straight ordered three of the new three-litre 8CM Maseratis direct from the factory and took delivery of two for the start of the season – together with three racing transporters, all of which being painted in the American racing colours of blue and white. These two 8CMs were passed over to Reid Railton for custom modifying at Thomson & Taylor. The modifications included different fuel tanks, different cockpit arrangements and the installation of a Wilson preselector gearbox.

The Wilson gearbox worked well enough but it sapped power and added weight. Frustratingly for Straight, the one time it failed cost him a certain victory in the Casablanca Grand Prix. The cars were certainly a talking point in the sport, and the most striking external feature of the Straight Maseratis was the replacement of the slab-fronted Italian radiator grille with a stylish heart-shaped cowl which was to become a Straight trademark.

Whitney Straight on his way to seventh at the 1934 Monaco GP

To drive with him, Straight signed Hugh Hamilton, Marcel Lehoux and Buddy Featherstonehaugh. Among the key figures involved with the team were future Jaguar giant “Lofty” England, Reid Railton and Bill Rockell.

Fortune also smiled upon Straight’s ambitions when it became clear that Alfa Romeo’s celebrated chief engineer, Giulio Ramponi, had resigned his position with Enzo Ferrari’s team. A deal was quickly struck and the Adrian Newey of his era came into the employ of this young American star.

Nevertheless, while there was racing genius behind the experimental developments being carried on his cars, even the might of Whitney Straight’s wallet met its match with the arrival of the government-backed giants from Germany. The works teams of Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union, with the full backing of their factories and the government, meant that even the indomitable Straight’s ambitions faltered beneath this technological blitzkrieg.

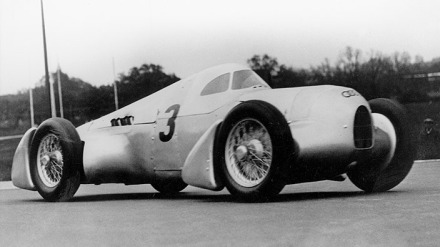

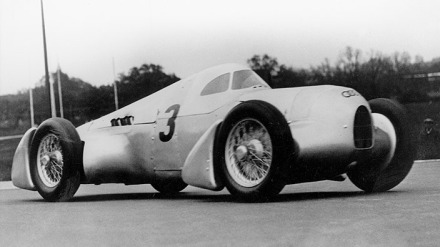

A 1935 Auto Union streamliner – Whitney Straight declined it

The 1934 season ended with a trip to South Africa. To make it a memorable occasion, Straight decided to fly his own aircraft, a de Havilland Dragon, down to East London for the race accompanied by Ramponi, his younger brother Michael and Dick Seaman.

Michael Straight had never raced a car before, but was entered in a four-litre Railton sports car developed by Jack Shuttleworth. Seaman was to drive Straight’s old MG, while Straight himself had the Maserati 8CM. Overloaded with fuel and racing spares, the plane ran out of runway while taking off in Rhodesia and landed in a ditch – but the party managed to effect repairs and carry on to reach their destination.

The six-lap handicap event is today considered to have been South Africa’s first Grand Prix – and Straight won it with panache. Nevertheless, this was to be his last competitive performance, for it was clear that conventional Grand Prix machines such as the Maserati were hopelessly outclassed by the Germans.

Straight (leading) knew that a privateer car couldn’t beat the Third Reich

Initially, Straight decided to buy one of the German cars. Mercedes dismissed his advances out of hand but Auto Union did seriously consider selling him one of its 1934-specification V16s. Ultimately the team chose – or was quite possibly ordered – not to allow a foreign team to enter a German car, but instead invited Straight to join the works Auto Union team for 1935.

Having spent much of 1933 and 1934 travelling through Europe, Straight was only too keenly aware of the ways in which the ‘silver arrows’ were a propaganda tool for the Third Reich – and that taking up such an offer could only be an endorsement of Nazism. While he had no interest in pursuing the pastoral, philanthropic ideals of his mother, father and stepfather, there was also no way that Straight could conscionably support Hitler.

Without a German car, Straight had no means of winning at the top level. So it was that after just one promising season the talented and determined young man abandoned his motor racing career. He made sure that Ramponi had a profitable business to run in Britain and also ensured that his services were available to Dick Seaman, who had completed a strong season in the MG through 1934 and, having reached his majority and inherited sufficient funds, was about to make the step to international racing in an ERA voiturette.

The ex-Straight 8CM in historic racing action

Straight, meanwhile, began to investigate the means of turning his passion for aviation into a profitable business. It became his new mission to ensure that, in the face of an increasingly bellicose and militaristic Germany, a culture of air-mindedness was fostered in Britain.

A new chapter was beginning in the life of Whitney Straight, of which more in Part 2…