At the climax of the month of May we arrive at a time to celebrate the fertility of the earth, for lambs to gambol beneath bright scudding clouds and for Indianapolis to become the focal point of the civilized world. This year’s Memorial Day marks the 100th running of the Indianapolis 500 and it is a thing of splendour to see Americans mark such an occasion with their inimitable panache.

The anniversary has resulted in anticipated crowd of around 400,000 – which is wildly up on recent seasons. This level of expectation in turn is causing some apprehension, not least among veterans such as Bobby Unser, who worry about whether the level of interest in a marquee day for America as will be seen this Memorial Day can be sustained. Others are predicting a brilliant race and the restoration of IndyCar racing as a whole.

Colourful, distinctive and unique: the 100th Indy 500 beckons

Certainly there will not be another global motor sport event with quite the same razzmatazz. The Grand Prix at Monaco has its place, of course, but in the modern world it’s all just a little bit queasy. Too many Russians on rented yachts, too many b-list pop stars warbling with Eddie Jordan on drums. Too much glitz and too little substance.

If you want a celebration of what motor racing has always been about then Go West, young man, Go West.

Even in their current state of eye-popping aerodynamics, fairground bumpers and paranoid paraphernalia to ward off injury, Indycars look mean and purposeful. Colours are sharper. Logos are brighter. And none of the cars from the imperious might of Team Penske to the clunkiest non-qualifier could be mistaken for anything other than an all-American phenomenon.

There’s always been a bit more dazzle and a soupcon of razzle

In the Eighties, the S&G was intoxicated by the speed and liveries such as the shimmering gold and chrome of Miller or the blistering Pennzoil yellow. There were also celebrations for Roberto Guerrero’s successes in America, after knowing him as a hard-trying and extremely courteous youngster among the Silverstone set.

Delving deeper into Indianapolis is to bathe in a unique folklore that never fails to inspire or to turn up the most incredible facts or personalities – not least, of course, Eddie Rickenbacker.

Super-fast Guerrero made his mark at Indy after struggling in Europe

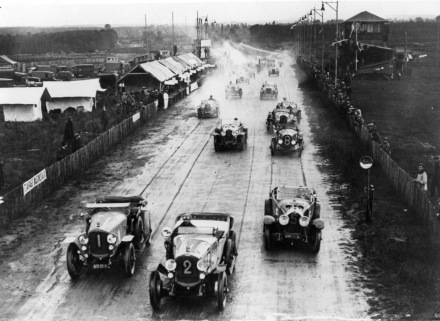

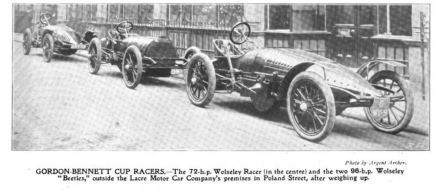

The first race ever held at Indianapolis wasn’t the 500 – which was first staged in 1911 – it was a motorcycle race won by Erwin George ‘Cannonball’ Baker on 14 August 1909. Construction of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway had been inspired by the world’s first permanent circuit at Brooklands in Surrey and thus a banked oval was chosen as the layout – although larger, flatter and effectively oblong.

It wasn’t the design of Indianapolis that caused problems in the early days, but rather the track surface, which was formed of ‘asphaltum oil’ and crushed limestone which had a nasty habit of dissolving people’s tyres. Before the first winter fell, the corrosive surface was buried beneath 3.2 million paving bricks, each weighing 9.5 pounds.

‘Cannonball’ Baker is also buried at Indianapolis: at the Crown Hill Cemetery on West 38th St. A long distance expert on two wheels and four, Baker’s spaciality was setting speed records from San Diego to New York – indeed the ‘Cannonball Run’ was named after him. Unlike many of those interred around Indianapolis, however, it was old age that claimed him.

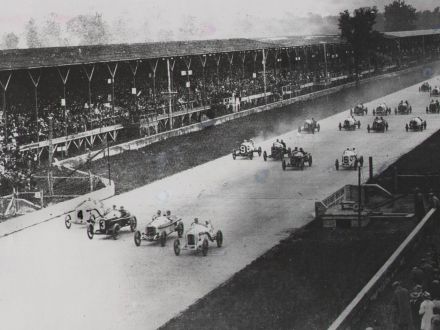

The spectacle of Indianapolis remains constant through the eras

Sharing space near ‘Cannonball’ Baker (together with the four founders of the Indy 500 and many other Indy 500 winners, drivers, mechanics and car owners) at the Crown Hill Cemetary, for example, is Wilbur Brink.

As a 12-year-old in 1931, Wilbur was playing in his front yard at 2316 Georgetown Road when, on lap 162, defending 500 champion Billy Arnold crashed in Turn 4. A stray wheel bounded across the road, struck Wilbur Brink and killed him outright – inspiring the song by Swedish pop band Norma: Bad Luck for Wilbur Brink.

That is the shade but it is 20 years since a fatality at Indianapolis and there is plenty more light than dark. It is the glitter on the faces hewn into the Borg-Warner Trophy – the easy smile that brackets the hard work and risk that is entailed when racing at Indianapolis.

The Borg-Warner Trophy is the single most impressive award in motor sport.

Of all the cars and eras that have passed at this great venue, among the most competitive and enduring must be the 1920s and the battle for supremacy between the supercharged straight-8 engines of Duesenberg and Miller. From the car that scored America’s first great victory overseas to the revolution in bespoke oval racing cars that followed, there is a steel-jawed brilliance in every aspect of the era.

After learning much from the great pre-1914 engines of Peugeot and Mercedes, which had also dominated at Indianapolis, the Duesenberg brothers, August and Frederik, returned the compliment by winning the 1921 Grand Prix in France. The Duesie’s straight-eight engine with single overhead camshaft was a masterpiece that triggered the development of home-grown sporting success in America.

Duesenberg went Grand Prix racing – and won

Having returned victorious from Europe the previous year, Duesenberg approached the 1922 Indy 500 with no small amount of confidence – although the race was in fact to mark the ascent of a new star. Harry Miller’s carburetors had been known as the best in the USA for some time and now he had designed a complete straight-eight with twin overhead camshafts and four valves per cylinder to the Duesie’s three.

The Miller also used a unique fuel blended by Shell that mixed benzol with gasoline to minimize knocking and allow for a significantly higher compression ratio. Duesenberg’s star driver, the Grand Prix winning Jimmy Murphy, tried out Miller’s engine and immediately had one fitted in his Duesenberg.

From that moment on, adding the 1922 Indy 500 to his Grand Prix title from the previous year became a formality.

Same car: different engine. Murphy’s Duesie is the only Grand Prix and Indy winner

In 1923 the cars became more streamlined, by virtue of making riding mechanics optional. This was because engine capacity was reduced to a mere 122 cu. in. (2 litres). Miller had meanwhile progressed from making engines to becoming a complete constructor in his own right, with the lightweight and spindly model 122 ‘convertible’ – so named because it could easily be adapted to many engine types.

It was with one of Miller’s new cars that Tommy Milton won the 1923 Indy 500, becoming the first man to win the Indy 500 twice. His Stutz-entered Miller crossed the line ahead of another Miller driven by Harry Hartz that was called the ‘Cliff Durant Special’, which was one of six cars entered by the heir to General Motors.

Duesenberg’s brief tenure at the summit of American motor sport had come to a very abrupt end – indeed, nobody but Miller won a major American event throughout the 1923 season. The Duesenberg brothers, August and Frederik, spent the winter putting the finishing touches to their response to Miller’s wonder-car: a centrifugal supercharger.

The ‘blown’ Duesenberg may have lacked grace compared to the Miller but it certainly had grunt. Muscle held sway in the business of going fast and turning left and the ‘blown’ Duesie with its signature howl was a revelation. The 1924 Indianapolis 500 delivered victory for Duesenberg team leader Joe Boyer, who took over the car of Lora Corum after his own car ran into mechanical trouble.

Before the end of the year Miller was reclaiming chunks of lost ground with a supercharger of his own – although the loss of Joe Boyer, killed in a race at Altoona, was a heavy blow. Having successfully supercharging his cars, Harry Miller wanted to find a new edge over the Duesenberg brothers for 1925. It came in the form of front wheel drive.

Original winner – the 1911 Marmon Wasp – beside a front-drive Miller in 1924

For years, American racing cars had been reliant on the same technology and layout that was used by the Europeans to go road racing yet the disciplines could not have been more different. European Grands Prix happened primarily on closed public roads, with changes in camber and elevation and corners that swept, jinked and plunged in both directions.

In contrast, American racetracks were exclusively ovals. Indianapolis presided over a national racing network of smaller tracks that were formed either from dirt or wooden boards like an oversized velodrome.

Harry Miller opted to listen to the ideas of Riley Brett, a young mechanic who worked on Jimmy Murphy’s car. Brett insisted that for driving on ovals, a special front-wheel-drive car would be perfect because it would eliminate the extra weight of a long driveshaft to the back wheels and it would allow the car to sit significantly lower to the ground, greatly improving its high speed cornering.

The concept was radical. In Europe, negotiating so many turns and angles and cambers in every direction, it would have been a disaster. Yet for American racing, Harry Miller believed that the idea had merit.

The man who was supposed to drive the new car, Jimmy Murphy, was killed in a fluke accident while racing on dirt at Syracuse but Miller continued with the front-wheel-drive concept. It was ready for Indianapolis.

Only 22 cars lined up on Memorial Day for the 1925 race but this would go down in history as one of the great Indy 500s. Although the field included no fewer than 16 Millers, of which just one was of the front-drive design, Duesenberg’s new star Pete de Paolo made the early running in his yellow ‘Banana Wagon’.

The Duesie stayed out in front for 50 laps and such were the strides being made by the manufacturers that, for the first time in Indianapolis 500 history, the race was averaging more than 100 mph despite successive cuts in engine size.

Pete de Paolo and the Duesenberg ‘Banana Wagon’

When de Paolo pitted to have his hands bound – they were being ripped to shreds by the steering wheel – sending Norman Batten out in the ‘Banana Wagon’ until he had recovered. The Millers of Earl Cooper and Ralph Hepburn ran together at the front with the yellow Duesenberg in third, began battling with the Miller of Harry Hartz. Hepburn had to pit and Cooper had a tyre blow out, sending him bouncing off the outside wall (but not into retirement – these were sturdy machines!), meanwhile the front-drive Miller of Phil Shafer moved up into the lead.

The little low-slung car was proving easier on both its fuel and tyres than the traditional rear-drive cars and Shafer was driving out of his skin. He managed to pass 350 miles without a pit stop and built enough of a cushion to pit for tyres and retain the lead.

The front-drive car ploughed on but Shafer was by now tiring – the front-drive was something of a brute to its occupants – and Pete de Paolo was back in the ‘banana wagon’ and closing in fast. The Miller team elected to call Shafer in to switch over to another driver, Benny Hill. The call came too late for Hill’s fresh eyes and arms to make much difference: Pete de Paolo would win the Indy 500 for Duesenberg at an average of 105 mph.

The front-drive Miller had shown its worth, however. After breaking the 100mph barrier in 1925, the rules were tightened once again for 1926 with a maximum engine size of 91.5 cu. in. Harry Miller responded by increasing the pressure of his superchargers and increasing the compression ratio – meaning that his little 1.5 litre engine was pumping out nearly 300 bhp.

Small but mighty: Miller’s front-drive masterpiece

At the 1926 Indy 500 it was an all-Miller show and another remarkable race. In practice a new kid, 23-year-old reserve driver Frank Lockhart, was kicking around Gasoline Alley and offered to take Benny Hill’s car out for a test run after the mechanics had finished working on it. Hill agreed and the team was stunned to see the car putting in its fastest times to date with Lockhart cornering on full opposite lock, foot on the floor.

Harry Miller gave Lockhart a ride in one of the older rear-driven cars. He set an unofficial qualifying record of 120.918 mph but his official time was only good enough for 20th spot on the grid. No matter – he was fifth by the end of the third lap and was soon in the battle for the lead. That was when the rain came.

Despite two downpours the race ended with Lockhart sliding imperiously to Victory Lane in front of the front-drive cars. It was to be the last race of this era of innovation in the battle between Miller and Duesenberg. Spiralling costs and falling entries meant that the rules were relaxed for 1927 allowing ‘stock block’ V8 engines into play. The front-drive Miller would finally win the Indy 500 but only in 1930, when the Great Depression was biting hardest.

Frank Lockhart crowned the high-tech era of the 1920s with victory aged 23

Nevertheless, the power struggles of the 1920s and the heroic drivers who competed in the era did much to cement the reputation of the Indy 500 across America and around the world. Their influence resonates throughout American motor sport to this day, making the 100th running of this astonishing race all the more significant.