One seldom thinks of central London as a focal point for aviation. There’s London City Airport, plus the interminable political blathering about where the next major runway should be built to service the city and, for schoolchildren, an occasional visit to the Royal Air Force Museum, Science Museum or Imperial War Museum.

Yet in fact a brisk stroll takes one through what was, a century or so ago, the white hot crucible in which British military aviation was organised – and from the Armistice onwards the peacetime air network would be established that so preoccupies our airport planners of today.

The Palace of Westminster is a fairly good landmark to get started

For the sake of argument, let’s start at the Houses of Parliament. Indeed, let’s start under Big Ben – if you can fight your way through the seemingly endless turf war between Japanese tourists with their selfie sticks and East European pickpockets – then you’ll soon arrive at the statue of the pioneering politician of air power, Winston Churchill. In his role as First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill showed uncommon vision for the potential of early aviation as a tool of reconnaissance and offensive bombing – resulting in the Royal Naval Air Service being significantly stronger and lighter on its feet than the army’s Royal Flying Corps.

Now head up Parliament Street to the Cenotaph and the beautiful facades of Whitehall abound. Keep going past Downing Street to Horse Guards Parade and there the magnificent War Office building stands opposite, from where the Royal Flying Corps was ultimately managed.

Built in neo-Baroque style to the tune of £1.2 million, the building was completed in 1906 and featured 1,000 rooms on seven floors connected by two-and-a-half miles of corridors. It was from here that wars were fought and won, occasionally fought and lost – and much of the Empire was policed until 1968. The building was sold on 1 March 2016 for more than £350M, on a long 250 year lease, to the Hinduja Group and OHL Developments for conversion to a luxury hotel and residential apartments.

The War Office – about to enter conversion to a hotel and residential development

Keep going just a little further and Admiralty Arch appears, with it Admiralty House and all the pomp of the Senior Service that is laid out like a challenge before anyone wishing to travel up the Mall. From here Churchill set about ensuring that the ground was made fertile for developing the first verdant shoots of a modern air force – while the dullards at the War Office retained their faith in horses in the face of mechanised slaughter.

Just like the War Office, Admiralty Arch has already been sold off for transformation into an hotel. The questions raised in parliament about how security for the many state and sporting occasions that run through Whitehall each year, let alone that of the Royal Family down the road, is to be maintained by hoteliers in the face of increased insurgency has never really been answered. But then Whitehall has suffered from more than its fair share of fatheads over the years – as we shall see…

The buildings around Admiralty Arch were a hive of air-minded activity when Churchill was First Sea Lord. Today it is a Spanish-owned hotel.

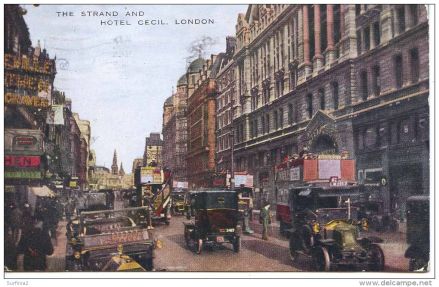

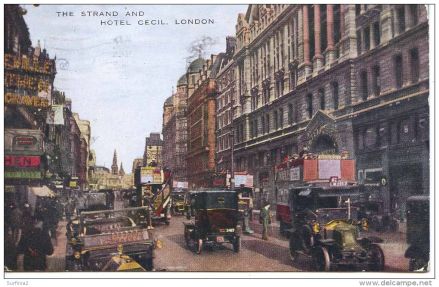

From the Admiralty, head up The Strand and there is a large run of shops lying in wait before reaching the Savoy Hotel. The shops stand at street level beneath an imposing facade that was once the frontage of the Hotel Cecil – one of the more remarkable buildings in London.

The Hotel Cecil was designed in the late 1880s by architects Perry & Reed in a sympathetic ‘Wrennaissance’ style for what was a fantastical barn of a building that would, in its day, be the largest hotel in Europe.

This 900-room leviathan was the pet project of notorious politician, financier, property developer and fraudster, Jabez Balfour. Balfour decreed that the Cecil should be “an abiding memorial of my enterprise” – although a rather more permanent memorial was the penury of the people who had invested in his schemes. The extent of Balfour’s embezzlement – a cool £8.4 million in 1895! – was uncovered during the Cecil’s six-year build.

The magnificent facade of the Hotel Cecil still dominates The Strand

In a colourful turn of events, Balfour went bankrupt and fled to Argentina, where he was pursued and apprehended by Scotland Yard, brought back to London and sentenced to 14 years of penal servitude. The Cecil was sold for a relatively paltry £1.5 million and the proceeds were redistributed among Balfour’s impoverished investors. The hotel’s construction carried on – although not all of the materials were as grand as had been hoped – but Balfour’s abiding memorial appeared set to remain a white elephant.

Despite recruiting such luminaries of the era as ‘Smiler’ the renowned Indian curry chef or M. Coste, one of the greatest chefs of the late Victorian era, the gargantuan hotel was a commercial black hole. It was therefore fortunate for the owners that war broke out in 1914 and suddenly a pressing need was found to quarter staff and administer the conflict.

In 1916, the increasing importance of the war in the air, combined with the profligacy and wanton disruption that the rivalry between the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service was causing meant that an Air Board should be formed to manage the quarrelling air services in a contained space. In January 1917 it was decided that the space in question should be the Hotel Cecil.

To the rear, the Hotel Cecil (and the Savoy Hotel next door) fronted the Victoria Embankment

The deep-rooted and bloody-minded rivalry between the two air arms carried on unabated, leading to claims that the occupants of the Hotel Cecil were ‘actively interfering’ with the running of the war. This in turn led to a nickname for their palatial residence: Bolo House, named after the celebrated French traitor, Bolo Pasha.

To digress – Bolo’s conviction was for a remarkable plot in which he was alleged to have travelled to America in order to receive laundered German funds with which he purchased Le Journal newspaper and began printing German propaganda. The evidence, such as it was, could only be described as circumstantial. Bolo’s firing squad was, however, utterly unequivocal.

The Savoy still looks out over the Victoria Embankment

Back to London, then, and one significant ‘plus’ for men of the air divisions was that if they were required to work in the Cecil they would be quartered next door in the sumptuous Savoy Hotel. Many celebrated airmen of all allied nations, including Eddie Rickenbacker, found themselves enjoying the hospitality of the Savoy, although the Silvertown explosion on 19 January 1917 caused many of the windows to be blown in upon the hapless occupants.

It took the bombing of London in broad daylight by long-range German aircraft to force change upon the Bolo House, brought about by the wave of public outrage against Britain’s inefficient defences against attack. While the administrative work went on that would create a united and independent Royal Air Force, the first ever plotting room was created in the bowels of the hotel in order to marshal defending fighters against incoming arial raiders in a precursor to the famous system employed during the Battle of Britain in 1940.

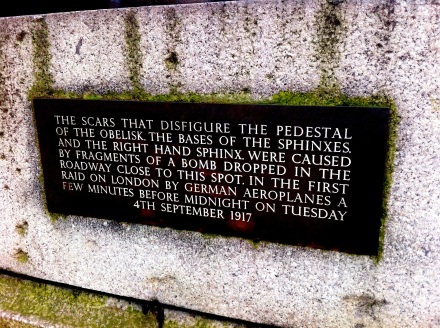

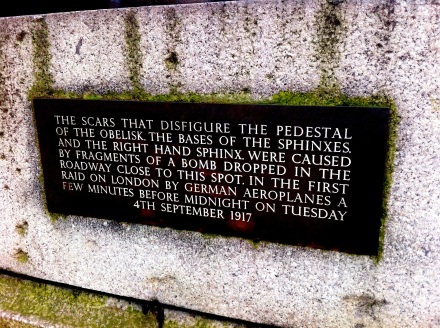

The plaque is almost correct – it was the first night raid by German aeroplanes

The German bombing campaign was also nearly the end of the Hotel Cecil, as on the night of 4/5 September the bombers came back for their first nocturnal sortie and managed to plant a 50 kg bomb virtually on the doorstep. The bomb itself landed beside Cleopatra’s Needle on the Victoria Embankment, onto which the rear entrance of both the Hotel Cecil and the Savoy faced.

The blast did kill and maim – a passing tram was caught in the blast, killing the driver and two passengers while blowing the conductor out onto the street. Today the site is clearly seen by the shrapnel damage that remains upon Cleopatra’s Needle and the Sphinx.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

As for the Hotel Cecil, it served out the war as the birthplace of the Royal Air Force and remained on governmental duties until 1921, when it was used to house the Palestine Arab delegation which arrived to protest the British mandate on the region. The site was then demolished in 1930 – save for the grand facade on The Strand – in order to make way for the beautiful art deco Shell-Mex House which presides over the Victoria Embankment to this day – Shell having provided every drop of aviation fuel used by the allies from 1914 to the end of 1917.

In 1961, after the official separation of Shell and BP, Shell moved its head office to the 27-storey leviathan on the South Bank of the river where it remains to this day. Shell-Mex House was disposed of in the 1990s and today it is known as 80 Strand, home of businesses as diverse as Penguin Books, the Nectar loyalty card and PricewaterhouseCoopers. A small green plaque was erected on the back gate in 2008 commemorating its status as the location where the Royal Air Force was founded.

The art deco frontage of Shell-Mex House (left) replaced the Hotel Cecil in 1930 to become a major landmark on the Thames, viewed from the bomb-damaged Sphinx

Walking back along the Victoria Embankment towards the Houses of Parliament, a golden eagle soon rises up overhead. This is the memorial erected immediately after the Great War in honour of the fallen airmen whose fate, in almost every instance, was in part decided within the buildings along the route of this stroll around the city.

The golden eagle sits atop an orb, around which a sash is wrapped carrying all the signs of the zodiac. Upon the pedestal, the inscription reads:

In memory of all ranks of the Royal Naval Air Service, Royal Flying Corps, Royal Air Force and those air forces from every part of the British Empire who gave their lives in winning victory for their King and country, 1914 – 1918.

There is also a quotation from Exodus 19: I bear you on eagles’ wings and brought you unto myself.

A further inscription was added in remembrance of those men and women of the air forces of every part of the British Commonwealth and Empire who gave their lives in World War 2, although this rather beautiful tribute has long since been overtaken by bigger-budget productions elsewhere, such as the magnificent Bomber Command Memorial in Green Park.

Just before reaching the end of this little walk around the crucible of British aviation, another of those modern memorials stands – that dedicated to the Battle of Britain in 1940. Just a few hundred metres from Westminster station, this low, flat block has the most ornate brass relief that makes an ideal spot to stop and tick off the places seen.

The Battle of Britain memorial on Victoria Embankment

Westminster and Whitehall are so very ‘pomp and circumstance’ that it is hard to credit the emergence of modern air warfare to buildings more closely associated with Trafalgar and the creation of of the British Empire. Yet it is perhaps an even greater leap to now think of these majestic buildings being turned into foreign-owned hotels for those guests who may be tired of life at the Savoy – or may indeed have something other than tourism in mind for their visit.

Meanwhile, this little patch of London is ripe with myriad stories. Far too many to write in a blog post, a book or even a trilogy. Tripping over them is the ideal way to spend an hour or so messing about by the river…

Shell-Mex House (centre) and The Savoy standing shoulder-to-shoulder behind Cleopatra’s Needle

Bader’s statue at Goodwood anchored the military vehicle area at the 2015 Revival

Bader’s statue at Goodwood anchored the military vehicle area at the 2015 Revival Bader (centre) and the men of 242 Squadron at Duxford, September 1940

Bader (centre) and the men of 242 Squadron at Duxford, September 1940

General Doolittle (in uniform) visiting Shell’s laboratories in 1945

General Doolittle (in uniform) visiting Shell’s laboratories in 1945 The Shell tanker Pecten, sunk on 20 August 1940 delivering 100-octane fuel to the RAF

The Shell tanker Pecten, sunk on 20 August 1940 delivering 100-octane fuel to the RAF