Auction house Bonhams is cock-a-hoop after the Goodwood Festival of Speed, where it sold the ex-Juan Manuel Fangio Mercedes-Benz W196 that was originally gifted to the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu.

Bonhams auctioned the 1954 Mercedes-Benz W196 at Goodwood

The headline figure stands at £19,601,500 (which is what the £17,500,000 hammer price comes to with commission), making this car the most expensive ever sold at auction, the most valuable Formula One car ever sold and the most valuable Mercedes ever sold to boot.

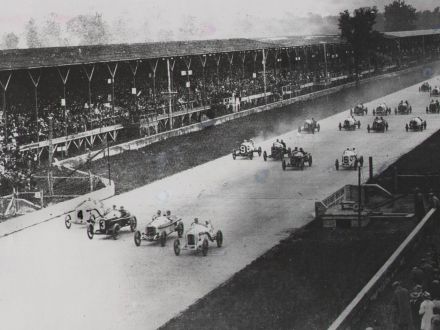

It is a mark of how special this car is that it attained such a sum. As a rule, single-seat racing cars go for relatively modest sums compared to their sports and GT brethren. The rationale is simple: if you can’t drive it to the pub or put your friends in it, it’s not going to make top dollar.

The social side of classic car ownership adds enormous value

People buy classic cars as an investment but also to show them off: to get the buzz of being at the wheel and to bask in the awe, envy and admiration that their carriages inspire. That is why the Ferrari 250GTO remains the powerhouse of the classic era – its unique beauty and racing pedigree ensure that values continue to climb, yet this is also a car in which Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason used to take his daughter to school.

The Mercedes therefore falls short of the $35 million mark set by the ex-UDT Laystall team GTO last year… but not by much. Since that time the pale green Ferrari has been a regular attendee at historic events, but whether or not the Mercedes follows suit is open to question.

Reaching $35 million in 2012, the UDT Laystall GTO is still king of the hill

A single-seat racing car can only be driven on a track, which means either competing with it or hiring a venue for a private track day. Otherwise it must either be kept hidden away in a private collection or loaned to a museum – neither of which fulfils the basic criteria of ownership.

The ultimate fate of the W196 00006/54 is unknown, but it seems likely to be leaving British shores. The vendor was the Emir of Qatar, who acquired it from the German industrialist Friedhelm Loh about eight years ago, and it was snapped up by an unnamed telephone bidder calling from overseas.

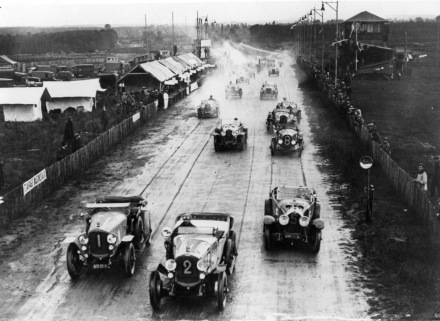

Presumably it will now go back into storage or private display. If money were no object then it might possibly be used in historic events alongside the many other 2.5-litre F1 cars such as the Ferrari 246 Dino, Maserati 250F, Cooper T53 and even the lesser spotted Vanwall.

’50s cars like this Aston Martin sell many tickets for historic races

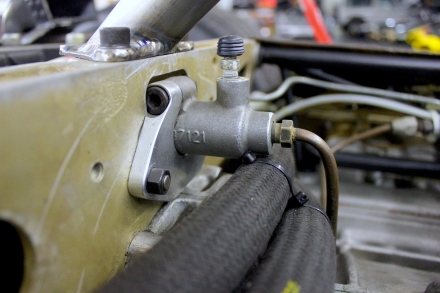

Yet this is a car with some fairly unique engineering in it – desmodronic valve gear and fuel injection feature on its straight-eight engine, which was engineered to ensure power take-off from the centre of its crankshaft to minimize vibration. Ground-breaking technology is unreliable. Add the passage of 60 years and it becomes impossible to place great strain on the components.

It would doubtless require significant restoration work to make 00006 a full-blown runner – but this is not a problem in itself. Since the auction, much has been made of the car’s patina – but the peeling paint and scratches are not a legacy from its time with the Mercedes-Benz Rennabteilung – in fact the damage is more modern than that.

The chips and dings have all occurred since 00006 retired from racing

Photos of the car at its first race at the Nürburgring show the slightly hurried and unfinished look of the open wheel body which was pressed in to service. Contemporary reporters were amazed by the difference between the carefully sculpted streamliner bodies with which the W196 debuted and labelled the open wheeler ‘unhandsome’.

Indeed, Mercedes had been forced to introduce the open wheel cars earlier than planned after a disastrous race at the British Grand Prix, meaning that the team arrived too late to take part in the opening practice session.

00006 and Fangio restored German pride at the ‘Ring

When they did take to the track, however, Fangio and chassis 00006 recorded a time of 9m 50.1s – shaving two seconds off the 1939 lap record set by the supercharged 3.0-litre Mercedes of Hermann Lang.

The race was in many ways an all-Argentinean affair, dominated by Fangio’s Mercedes and a valiant challenge to its supremacy by Froilán González in the outclassed Ferrari 625. Both men were in no small part inspired by the death of their young compatriot Onofre Marimon in practice, whose fatal accident at the Wehrseifen bridge prompted the works Maserati team’s withdrawal.

Fangio’s race pace was modest, but he and 00006 triumphed in Germany

González led at the start and then chased Fangio once the Maestro had got past – but was soon swallowed up by the other two Mercedes of junior driver Karl Kling and pre-war legend Lang in a one-off appearance. These two men indulged in a spirited battle for second place in which the ring-rusty Lang ultimately spun at the Hatzenbach and exited to a hero’s salute from the crowd.

Kling then set off after Fangio and began to reel him in – to the enormous and obvious displeasure of his team boss, Alfred Neubauer. Kling passed Fangio but during his furious drive he had clipped one of the banks and broken the transmission mounting, requiring a lengthy stop for repairs which let Fangio claim the first home victory for Mercedes in 15 years.

Fangio then won again with chassis 00006 at the Swiss Grand Prix at Bremgarten, beating the Ferrari of González. The race was something of a non-event in which the margin of victory was almost a full minute after many of the fancied runners dropped out – but it did seal Fangio’s second world championship title.

Victory at Bremgarten ensured the 1954 title for Fangio

The maestro then received a new chassis and 00006 was next seen at the season-ending Italian Grand Prix in the hands of Hans Herrmann. Fangio won by a lap from Hawthorn’s Ferrari, González and Umberto Maglioli sharing the third-placed Ferrari another lap behind and Hermann trailing home fourth a further lap in arrears.

00006 was then held back as a test hack through 1955, when the season was truncated by the catastrophic accident at Le Mans. It re-emerged for the final race of the ‘silver arrows’ in Formula One – the 1955 Italian Grand Prix. Team leader Fangio and his young apprentice Stirling Moss had use of the fully streamlined cars for the flat-out sweeps of the Villa Reale, but the open-wheel chassis 00006 was made available for Karl Kling.

Kling and 00006 are third in the W196 train behind Fangio and Moss

It was another fiery and wayward performance by Kling, who ran a strong second behind Fangio’s Stromlinienwagen until the prop shaft let go, due to a rare error by Neubauer’s engineers. With that ‘Don Alfredo’ Neubauer tearfully drew a veil over the competition department at Unterturkheim and the 14 W196s went into retirement.

Fangio and Moss help Neubauer put the legendary ‘silver arrows’ to bed

Chassis 00006 was delivered to the Daimler-Benz Exhibitions Department in December 1955, having been fully refettled. It stayed with them for more than a decade, being taken to exhibitions and public appearances around Europe and being used for tyre testing. A Daimler-Benz Museum archive document records that as of November 5, 1969 “Car should be available at any time for R. Uhlenhaut for testing purposes”.

On May 22nd, 1973 it was presented to the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu, Hampshire, England. It was then sold after many years in order to fund the museum’s John Montagu Building, being bought by historic racer and collector Sir Anthony Bamford of JCB Excavators in a deal brokered by Adrian Hamilton, son of Le Mans winner Duncan Hamilton.

Sir Anthony Bamford bought the W196 from Beaulieu

Bamford sold the car to French collector Jacques Setton. It then passed to Herr Loh, who in 1999-2000 ran it in such events as the Monaco Historic Grand Prix and the Goodwood Festival of Speed with Willie Green at the wheel. The car was then re-sold to Qatari ownership.

Now, in 2013, this old stager has set a new benchmark for cars at auction – but are there any more such valuable Grand Prix racing gems out there? It must be doubtful. There are certainly cars in existence that would trouble the Richter scale if they were to see the light of day – but they remain tucked up far away from the public gaze. Perhaps once again a car built at Unterturkheim has set the bar higher than any rivals can match.

Off to her new home – 00006 as she is today