We’re going to venture beyond the S&G’s remit here, ladies and gentlemen. Part 1 of the Ken Miles story took us past the 1961 cut-off for our yarns so let’s blaze onward unrepentantly, in the manner of the subject of this double-header.

In 1963, the mechanics in Carroll Shelby’s workshops – the famous ‘Snake Pit’ – called the angular Englishman in their midst ‘Teddy Teabag’ because of the endless British brew-ups with which he sustained himself. Either that or ‘Sidebite’ in reference to his habit of speaking out of the corner of his mouth.

He was respected… although everyone agreed that kid gloves were needed to handle him on occasion. The man in question was called Ken Miles, and this is how the rest of his story went…

By the end of 1963, the AC Cobra that Carroll Shelby and Ken Miles had built was riding high. Fundamentally it had achieved all that Shelby had set out to do: it had beaten the Chevrolet Corvette to become the dominant force for outright victories in American GT racing. And it had done so with a Ford V8 under the hood.

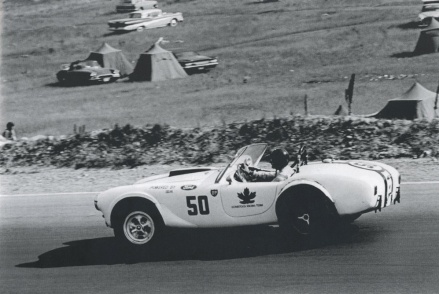

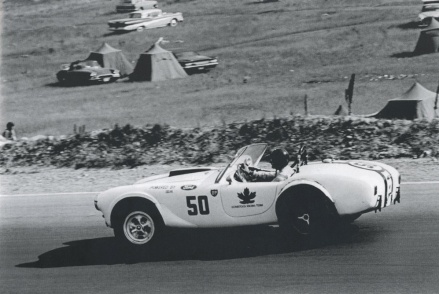

Miles competing ‘on loan’ to Comstock Racing for the Canadian Grand Prix

This in turn caught the eye of Ford executives like Lee Iacocca, who was about to launch the Mustang and a new way of thinking called ‘Total Performance’ that was intended to prove that Ford was not just the dour choice of cranky old American ladies who refused to buy a Volkswagen.

The final piece in the puzzle came in the form of Henry Ford II himself – known to most as The Deuce – who could see that America was almost fully mature as a market in which to sell cars but that Europe remained to be conquered. As the 1960s really hit their stride and the European years of post-war austerity finally abated, The Deuce wanted to revitalise Ford’s image at home and dominate the emerging European markets with his products.

Lee Iacocca was the architect of Ford’s metamorphosis. “Speed sells.” he said.

First he had planned to buy Enzo Ferrari’s operation in Maranello and launch a range of high performance Ferrari-Fords (or Ford-Ferraris). Negotiations were held, but Ferrari puled up the drawbridge when the final contract lay on his desk. He threw the Americans out, so instead The Deuce decided to beat Ferrari at the most famous race of them all, the Le Mans 24 Hours – no matter what it cost.

Thus Ford embarked upon the GT40 programme in late 1963, after Shelby introduced the Ford executives to Lola’s Eric Broadley (who would design the car, together with Ford stylist Roy Lunn), and former Aston Martin team boss John Wyer (who would run the operations). Unfortunately, the GT40 programme went from one disaster to the next in its debut year of 1964.

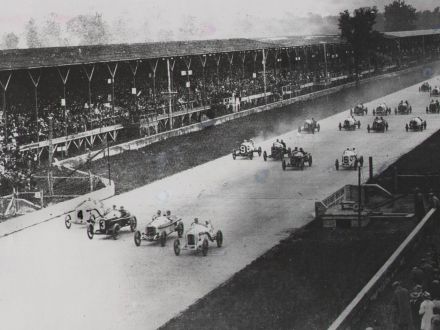

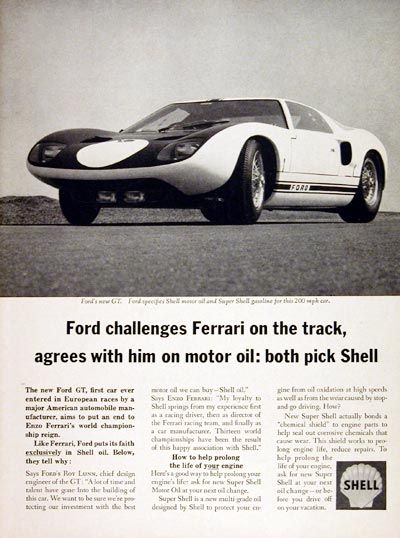

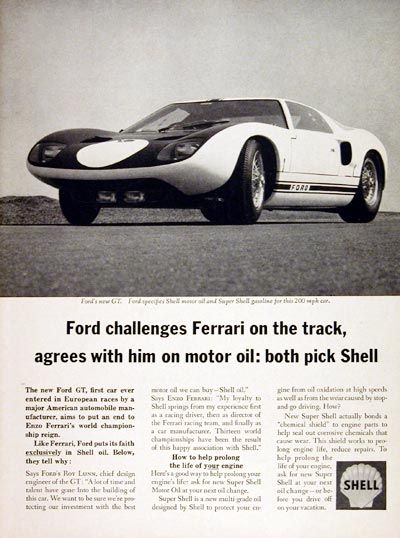

Shell forgets the 1921 Grand Prix-wining Duesenberg in its 1964 adverts

Meanwhile at the expanding Shelby American factory, the Cobra was also benefitting from Ford’s largesse and with a streamlined body designed by Peter Brock (no relation). The so-called Cobra Daytona Coupé was about to be unleashed onto the world stage.

By the end of 1964, the Daytona Coupé had provided the only ray of light in Ford’s season, beating Ferrari to the GT class at Le Mans. It would have won the World Championship for Makes as well, but for the decisive Monza 1000 km being cancelled at the behest of Enzo Ferrari. It was a low blow, but from behind those impenetrable dark glasses, Ferrari was able to see that he was having to play for time.

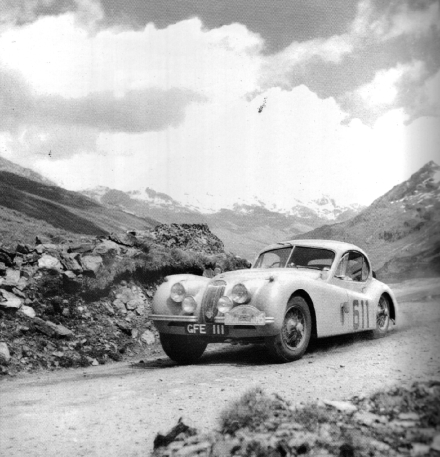

With Peter Brock’s body on it, the Cobra squared up to Ferrari in Europe… and won

Meanwhile at home, Ken Miles himself finished on the podium in more than half of the domestic American sports car races that he entered at the wheel of one of the original and wild little open-top Cobras.

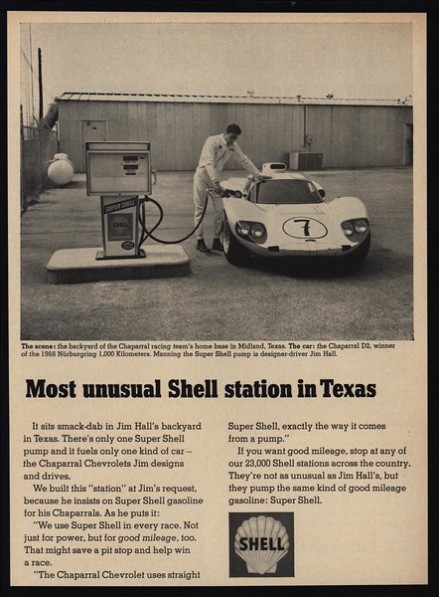

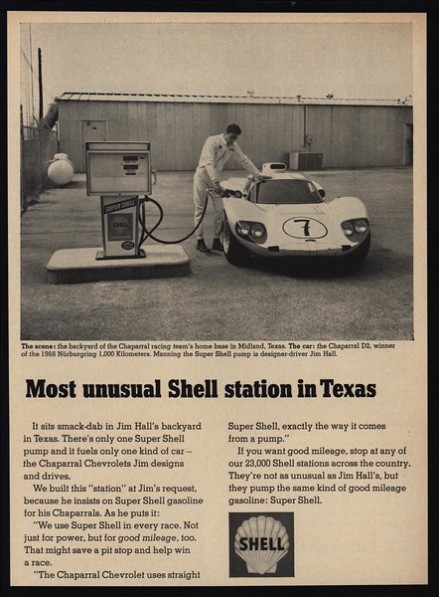

The GT40 remained a failure, though. Adding insult to injury, Chevrolet had begun to throw money at Jim Hall and his Chaparral operation to try and out-do the GT40, while the Bill Thomas Cheetah had become a GM-sanctioned rival for the Cobra. If Ford’s pursuit of Ferrari wasn’t troublesome enough, it now had to fight a rearguard action against The General.

GM-backed Chaparral came after Ford’s motor sport programme with every resource at its disposal

This led to another concern for the men at Ford… one that grew through 1964. Not only were the GT40s struggling to be competitive, but also Chevrolet’s racing programme had an unalloyed American blood line. Both the Cobra and the GT40 were British cars with Detroit muscle, so a decisive move was made to ramp up the stars and bars attached to Ford’s racing endeavours.

Carroll Shelby and Ken Miles were given the GT40 project, lock, stock and barrel, to rework for the 1965 season under the Shelby American banner. The spending increased dramatically in the winter of 1964-65 when the decision was taken to freeze development of the original 4.7 litre GT40 cars and plough resource into a monstrous new 7.0 litre Ford GT Mk.II.

There was precious little improvement in Ford’s racing fortunes in 1965, despite the massive hike in engine power, but The Deuce and his men in Detroit gave Shelby the benefit of the doubt. Meanwhile Miles and the engineers sweat blood to make the new car work.

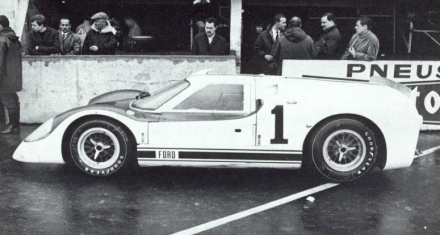

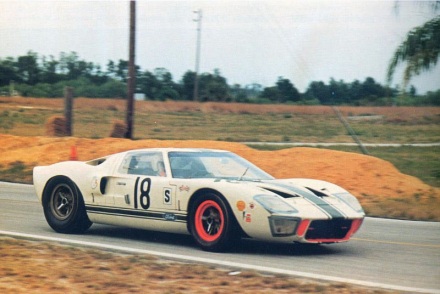

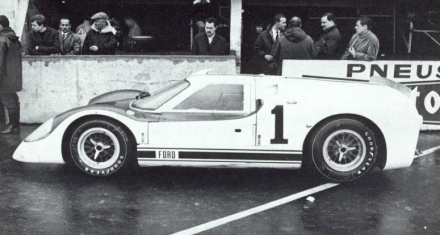

The first 7.0-litre Ford Mk.II appeared in 1965, developed by Miles

Miles himself spent countless days tramping around the circuit at Riverside, often with NASA-spec equipment to measure airflow and temperatures. He relished the abundance of new technology for data acquisition and processing, the astonishing computerised dynamometer that could recreated every lap of Le Mans for a full 24 hours.

And he loved caressing the wheel with his fingertips as the results came back in laps driven faster and more reliably than ever.

By the start of 1966 the work was almost completed – at a development cost of something like $15 million per year, or $116 million in modern currency… an unprecedented sum for the mid-Sixties. Not since the silver arrows had flown for Nazi Germany had any racing programme been so lavish – or indeed so political.

Perhaps in hindsight this was not the best environment for ‘The Hawk’. But without him the story would have been rather different. As it was, the highly-regarded engineer and development driver found that his racing speed was sufficient to cause some unwanted waves among the Ford men in 1966.

At the start of the season it was Miles and Lloyd Ruby who took the first international victory for the 7-litre car – and the first major race win for the GT40 programme – at the 1966 Daytona 24 Hours. There were scenes of pandemonium as they crossed the line and, finally, the promise that the GT40 had been shown in full to the public… and those hundreds of millions of dollars spent were about to find their rich reward.

Miles (right) and Lloyd Ruby celebrate their Daytona success

Nobody at Ford cared who won at that point. They just saw the metaphorical blue oval on the nose and got on with shouting from the rooftops. Even Ferrari was generous in its praise for Ford’s tenacity in sticking with the programme until it came good.

Next came the 12 Hours of Sebring and, to enormous surprise, Miles and Ruby were the winners once again. However, this was the moment when the Ford execs took issue because the wiry Briton had blatantly disobeyed team orders and, instead of holding a comfortable second place, had pushed the leading Ford of Dan Gurney and Jerry Grant into speeding up and breaking its gearbox.

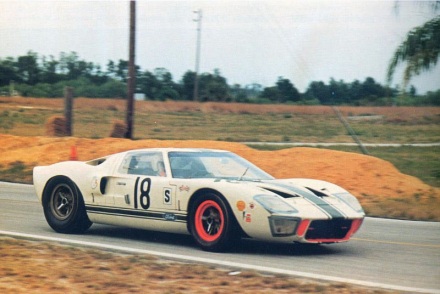

Miles chased down Gurney’s leading sister car to win at Sebring

In the eyes of the Ford execs, Miles had committed an unforgiveable sin. Yet ‘The Hawk’ had no truck with any sort of request to hold station and was not inclined to trust ‘suits’ – even those spending upwards of a quarter of a billion dollars on the programme that he served.

Now came preparations for ‘the big one’ and the Fords arrived at Le Mans in force. In the meanwhile, Miles’ regular co-driver Lloyd Ruby had been badly knocked about in a ‘plane crash, so the burly and equally bullish New Zealander Denny Hulme was drafted in to share the number 1 car with him.

And so the race played out: the Miles/Hulme Ford setting the pace for most of the race while many of their stablemates and the pursuing Ferraris began to hit trouble.

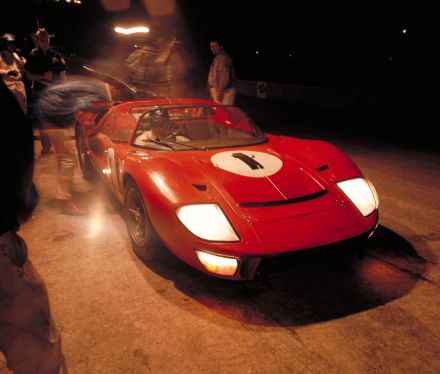

Miles and Denny Hulme kept car no.1 in front at Le Mans

Meanwhile, the black GT40 of all-Kiwi crewmen Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon had fallen back early in the race when their tyres began to fall apart. Both men were contracted to Firestone whereas the rest of the Fords were running on Goodyears, so the decision was taken that Ford would compensate Firestone if they switched brands… and this they did.

Famously, as Amon set off for his first stint on Goodyears, Bruce McLaren opened the door and yelled over the roar of the big V8: “Go like hell!” This they both did – although the intention was that they should complete an all-Ford podium rather than win the race.

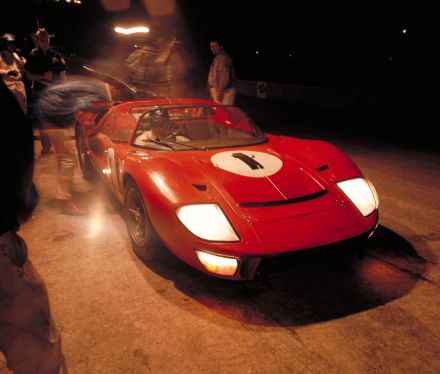

In the closing stages, Ford’s man on top of the racing programme, Leo Beebe, suggested that their two leading cars – Miles/Hulme and McLaren/Amon – should close up and cross the line on the same lap in a dead heat. The Deuce was easily convinced and, as their final pit stops approached, Beebe gave Miles the instruction.

It is a colossal understatement to say that Miles, who was on course to become the first man to win the endurance racing ‘triple crown’ of Daytona, Sebring and Le Mans in a single season, was incensed. He tore off his sunglasses and hurled them down the pit lane. “So ends my contribution to this bloody motor race.”

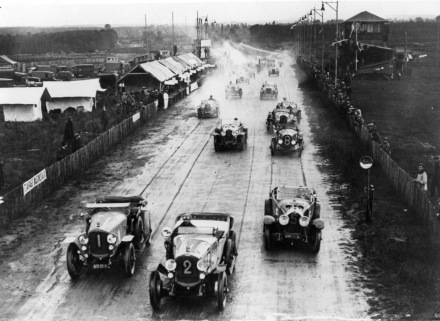

Photo finish: the Fords complete the 1966 Le Mans 24H

Only after he took the number 1 Ford back out onto the track for its final stint were the Ford team members told that a dead heat was all-but impossible, because the black number 2 car being driven by McLaren had started 60 feet further back than the blue car of Miles, thereby covering a greater distance.

Many hands were wrung. Should they tell the drivers? Should they cancel the stunt? In the end, the men from Detroit remembered Miles’ disobedience at Sebring and let history be written. The number 1 and 2 Fords crossed the line just ahead of the number 5 Ford in their wake.

At the finish line, McLaren gave a last blip of the throttle and pulled to a halt in front of Miles. The New Zealanders weren’t sure what was going on but Miles and Denny Hulme were sure that they had won. It was only when they tried to drive to the winners’ position and were turned away did the reality dawn upon them.

“I think I’ve been f***ed,” Miles said.

The slightly bemused pairing of McLaren and Amon, together with car number 2, went to the podium in the company of Henry Ford II and the suits from Detroit to hear strains of the Star Spangled Banner being played in their honour. They would soon be climbing aboard The Deuce’s private jet to a global whirlwind of parties, interviews and lavish celebration.

Before leaving the circuit, McLaren went back to the pits to collect his gear. He found Miles there, alone and in utter desolation. The two men looked awkwardly at one another for a moment before Miles stepped forward and pulled his team mate in for a congratulatory bear hug. To a waiting British journalist, Miles later said: “I’m disappointed, of course, but what are you going to do about it?”

Forty years later, Carroll Shelby remarked: “I’ll forever be sorry that I agreed with Leo Beebe and Henry Ford to have the three cars come over the line at the same time… Ken was one and a half laps ahead and he’d have won the race. It broke his heart.”

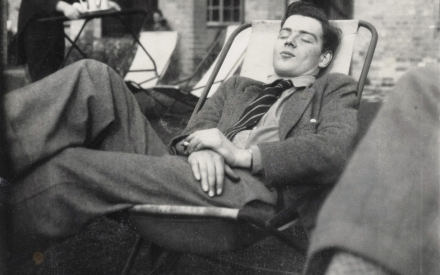

Miles in happier times

Back at Shelby American, the successor to the Ford GT40 was being developed: the Ford J-car. This car looked more radical, with a square ‘breadvan’ rear end and a lobster claw nose. It was lighter and stiffer and most importantly of all it was all-American. It had been decreed that Ford would go back to Le Mans in 1967 and win with an American car and drivers.

Two months after Le Mans, Ken Miles was finishing another long day of pounding round the Riverside race track in the J-car. Coming down the back straight he lifted off, the engine note fell and he shed some speed while preparing to cruise back into the pits. But inexplicably, the J-car then speared off the track at right-angles.

Ford’s all-American J-car as it appeared in testing at Le Mans

It took off, cleared the embankment and bounced end-over-end down an escarpment before bursting into flames. The following Saturday, Ken Miles was cremated and slowly slipped from the collective memory.

The J-car was meanwhile reworked to become the Ford Mk.IV which did indeed win the 1967 Le Mans 24 Hours with an all-American crew of Dan Gurney and A.J. Foyt on board. The sheer might of the Mk.IV caused the FIA and the Automobile Club de l’Ouest to immediately ban cars with engines larger than 5 litres and the sleek ’67 Ford never raced again.

Ford flirted with a new sports car, the 3-litre P68, but this soon began to fly off the road with alarming regularity. There was little point in continuing at Le Mans officially, so Ford refocused on its Formula 1 engine programme with Cosworth, while putting showroom models out on rallies and touring car races to maintain its link back to customer product.

But this is not the end of the story.

Twenty years and more after the drama of 1966, a former police officer called Fred Jones, by then enjoying his retirement as a Cobra collector and Ford motorsport nut, went in search of some documents missing from his archive. He discovered not one but two death certificates for Ken Miles in the Riverside coroner’s office. This did not sit easily with a man who dealt with that sort of paperwork on a daily basis. He started digging.

He also found and was told several different accounts about the crash: variously that Miles was decapitated, that he was dead when the medics arrived, and he was still breathing when the ambulance doors closed. Doubtless he was intrigued by the testimony of Miles’s son Peter, who was there at Riverside in August 1966, and said: ‘I remember seeing the car burning but I didn’t see my Dad.”

Eventually the path that Fred Jones found himself on led to a little town called Scandinavia in Wisconsin, where he met a wiry, destitute old man with a large and crooked nose who lived in an abandoned school bus. He introduced himself as Ken Miles, the racing driver. He produced a drivers’ licence in the name Kenneth Henry Miles, born in 1918, as evidence and told many stories about life at Shelby American, about Le Mans and Sebring and Riverside and Daytona.

The dishevelled septuagenarian claimed that Ford had paid him $2 million to disappear. The obvious response at this point is either to shake one’s head or simply ask ‘Why?’ But hey, this was the Sixties, man. Just one more all-American conspiracy to sit alongside JFK, RFK, MLK, Malcolm X, LSD and that, like, totally fake moon landing!

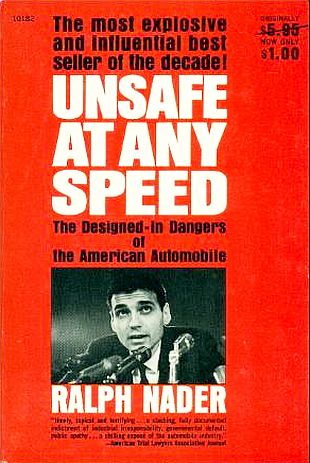

So where was the conspiracy to attach to Ken Miles? Well, it just so happened that in 1966 the road safety movement burst into vibrant life and the ethical premise of motor racing – i.e. selling cars with speed – was being publicly called into question.

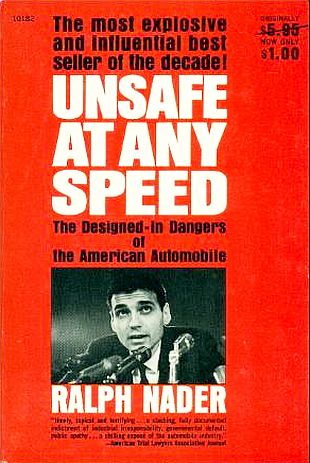

The standard-bearer for this crusade for road safety was an academic and ambitious would-be politician called Ralph Nader. In his highly proactive anti-car campaign, Nader highlighted the fact that the death count on American highways was increasing exponentially.

Nader’s research drew attention in the press and he played to the gallery, effectively accusing motor manufacturers that promoted themselves through speed of signing the death warrant of innocent road users. And he singled out Ford Motor Company as the biggest culprit.

Inertia was not an option for the US administration and swiftly the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act was enacted and the government took a direct hand in what its motor manufacturers were doing about road safety. There was grist to the mill when, even as the Act was being drawn up and passed, Ford’s motor sport programme suffered its first two deaths.

First, Canadian driver Bob McLean was burnt to death at Sebring in a GT40 owned by Canadian team Comstock Racing. Then at the Le Mans test, Ford works driver Walt Hansgen was killed just as Nader and the road safety reform wave had crossed the Atlantic from America and broke on the shores of Europe.

Bob McLean was killed in this car when it struck a telegraph pole at Sebring and caught fire

Thus, 20 years later, the old man in Wisconsin told Fred Jones that while he, Ken Miles, had recovered as best he could from the J-car crash at Riverside, Ford paid him to go away and a cremation was held before a grieving Californian motor sport community. His ashes were not placed in any known grave or mausoleum. He vanished.

It has all the ingredients of a decent conspiracy but, let’s remember, this was America. In the Sixties. In fact, there were Ford employees in 1966 who went to their graves believing that Ralph Nader and the road safety lobby was a scam funded by General Motors to stop Ford’s motor sport campaign in its tracks. The old double-bluff conspiracy!

And if you want to know whether the American public has lost its taste for conspiracy theories, we humbly suggest that you check the incumbent President’s Twitter feed.

Eventually, Fred Jones went back to the surviving team members and reported the story that he’d been told. Most of them told him in no uncertain terms that the story was complete hokum – although why an old destitute living in a bus might claim to be Ken Miles and offer up a fairly convincing picture of life at Shelby American was anyone’s guess. A photo of the man who claimed to be Ken Miles can be found here.

Fred Jones’s journey ended when he presented his story of the old man in Wisconsin to Carroll Shelby himself while lunching in a hospitality suite at the Monterey Historics weekend. He claimed that the legendary Texan dropped the plate of food that he was carrying, but said nothing.

It is an intriguing, infuriating end to the story of a man who was dedicated to motor racing like few others: a Renaissance man who drove, engineered and administered his sport, who was competitive right up until his late 40s and whose contribution to the American and European heritage of racing is almost unfathomable.

As an aside, at the time that Fred Jones ‘discovered’ Ken Miles in Wisconsin, his son Peter Miles was launching a career in motor sport engineering with Florida-based Precision Performance, Inc, taking part in the 1991 Baja 1000. He has since helped publish a beautiful scrapbook of photographs and magazine articles about his father, published by Brooklands Books, that is available here.

Ken Miles, 1918 – 1966

The S&G salutes you.