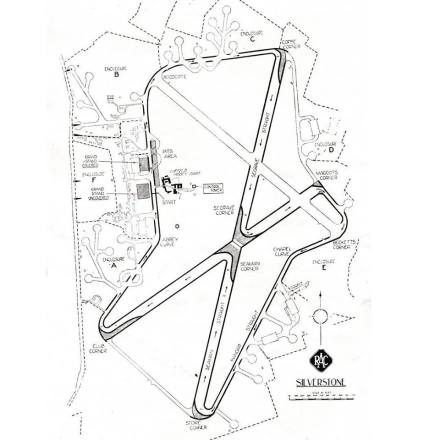

The announcement that Silverstone – and therefore the UK – will be missing from the FIA World Endurance Championship calendar from now on is not a surprise. There has been much hoo-ha on social media about it from British ‘fans’ – although it’s quite likely that more people have taken the trouble to post their outrage than ever bought a ticket.

Of rather more pith and moment is the fact that at present the Royal Automobile Club’s Tourist Trophy has no home – and there is no obvious candidate to replace it. But why, after so many decades, is top flight sports car racing abandoning the UK?

In 2011, the S&G worked on behalf of the Automobile Club de l’Ouest to promote the event. A phone call in mid-July basically said that there was a budget to promote the race, which was in mid-September, and as everyone in France takes August off would we mind awfully doing what we could to sell some tickets.

The Tourist Trophy has been awarded to the winners of the Silverstone 6 Hours in recent years

It was the dream brief: a client who gives you a budget first and asks questions later. It was quite possibly the most fun that will ever be had in this working life.

Local radio stations from the Solent to the Black Country ran adverts that used Steve McQueen’s movie Le Mans as the theme, with a heartbeat getting faster and engines bursting into life while a sonorous voice spoke in wonder about the world’s most advanced sports-prototypes and the elegant GT cars, Audis, Peugeots, Aston Martins, Porsches, Corvettes and Ferraris.

Every station that took the ads got pairs – sometimes several pairs – of VIP hospitality tickets to use as competition prizes. So did any local newspapers that we advertised in, which from memory was about a dozen from Herefordshire to Suffolk and Watford to Uttoxeter.

On the PR front, we realised that it was the 35th anniversary of the first Silverstone 6 Hours race, and got the winner of that inaugural race, John Fitzpatrick, to describe his giant-killing act alongside Tom Walkinshaw in a home-brewed BMW against the might of the BMW and Porsche works teams. We also got Desiré Wilson to talk to the press about being the first and only lady racer to win the event.

The girls of the Silverstone 6 Hours with Dunsfold’s P-51D

There was a media day at Silverstone where home favourite Allan McNish took journalists round the track in a race-prepared Audi R8 GT car. Among the victims we sorted out for the day was BBC Radio 2 Drive Time sportscaster Matt Williams, who did a brilliant piece for roughly five million listeners which basically involved him asking questions in a panicked scream and Nishy laughing like a drain in reply.

Northampton railway station was completely wrapped to look like the grid at Le Mans (a little tribute to how our Bahraini friends promote their Grand Prix so well), and at every station between Euston and Birmingham there was advertising to be found on the platforms.

Finally, we found some of the finest-looking promo girls in Britain, dressed them in replicas of the iconic and much-lamented Hawaiian Tropic girls’ outfit and sallied forth to as many other motoring events as we could – armed with a barrel-load of flyers with unique 10% discount codes. At Dunsfold Wings & Wheels we took along one of Trackspeed’s Porsche GT3s and a Gulf Aston Martin DBR1/2, at Chelsea Autolegends we had the Aston and the Strakka Racing HRD that slotted in to the Le Mans-themed main display, and the ACO came and did a press conference.

On the lawns of the Royal Hospital at Chelsea alongside a few billions’ worth of classics

If in doubt, grab a Chelsea Pensioner.

Because enthusiasts of motor racing tend to like having models of the cars in some shape of form, we did a deal with the now sadly defunct Modelzone company to put posters in the windows of their 46 shops across the country and for each shop to have a prize draw for a pair of hospitality tickets. They also ran a competition on their website and to their email distribution list to win the opportunity to wave the flag that starts the race.

We had branding all over Autosport.com, a competition to do the grid walk on Pistonheads and yet more competition prizes of hospitality. As a final offer, we contacted the marque clubs of every brand with cars taking part in the event and offered them display parking on the infield with a sliding scale of up to 50% off the ticket price, the more cars (and therefore people) that came with them.

As a final treat to reward the hordes of people that we hoped would be coming, we got the distributor of SCX slot cars to set up a tent with a massive track in it and plenty of Audis and Peugeots to race. We got John Fitzpatrick and Desiré Wilson to come along and do autograph sessions. We got Porsche 956 chassis 001, the 1982 Group C class winner and founder of 12 years of success for Porsche, together with a BMW CSL representing the inaugural 6 Hours and a Porsche 935.

All of this was done in six weeks from a standing start. All of this was done on a total budget that would scarcely pay for a tatty second-hand Porsche. All of this reached an audience of millions and we sold… something like 8,000 tickets. It was raining at Silverstone and there is seldom a more desolate part of the world on a soggy September day than the old airfield, especially when one is wandering round looking at the fruits of one’s labours and seeing not one soul between Copse and Stowe other than the ever-hearty marshals.

With heavy hearts we reported in to the ACO folks, expecting to be informed that we’d never work in this town again. They were… coq-au-hoop! Refreshed from their month in Provence, they couldn’t believe that they’d sold around 15% more tickets than the previous year with a campaign that lasted six weeks instead of three months.

It’s Silverstone, they said, with suitably Gallic shrugs. Everything costs too much because they have to fund the Grand Prix. The Wing stood empty above the paddock because it was too big and infeasibly priced, so all the hospitality had to be done in the old units on the old start/finish straight and guests had to be bussed the mile in between lunch and the working area.

We even had a page in The Sun – although the cars were notably absent…

The only location that could be found for the marque clubs, slot car track and historic racing cars display was exactly half-way between the two paddocks, meaning that few people bothered to get off their buses and brave the rain to come and have a look. As it was, neither the tent for the historic cars or the security person to look after them had shown up, so we had to send the Porsche 956 back to its owner and keep the BMW and 935 outside while a short-notice tent was found to house them.

When the S&G returned to the event in 2014, it was the first round of the new season and there had been much excitement on social media about the return of Porsche and all the rest of the pre-season chatter. There had been a photo call with the cars in central London but very little in the press had resulted from it, there were no adverts to speak of and no campaign of the sort that we’d done but the weather was uncommonly pleasant on the Saturday.

Le Mans brings fans together from around the world – especially the UK

There was still barely a soul in the public areas around much of the circuit. If more tickets were sold the difference was marginal. Yet at Le Mans one can barely walk a step without falling over roaming families, all eagerly discussing the race in every accent and dialect of the British Isles. Chuck a rock into the crowd at Le Mans and you’re far more likely to be told to ‘eff off’ than you are to ‘va te faire foutre’.

So now the ACO has decided to abandon its crusade to give British fans a treat on home soil. It’s not possible (as so many of them have wished) to return to Brands Hatch because the circuit isn’t to modern endurance standards – and anyway the 1000km races there in their 1980s heyday were fairly processional because there’s no room for overtaking.

People remember those races so fondly because there were big crowds, in part due to the presence of Jaguar and Porsche’s great ace Derek Bell as national heroes… and also in part because everyone buying a ticket to the Grand Prix at Brands got a free ticket to the 1000km. Sometimes, nostalgia ain’t what it used to be.

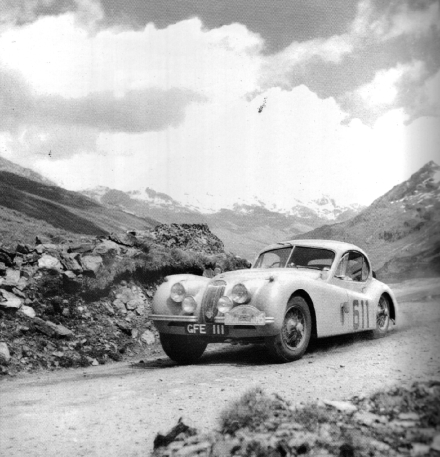

Brands Hatch had a packed house for Group C sports cars in the 1980s

So, a chapter closes and all that remains to be said is what the future holds for the Royal Automobile Club Tourist Trophy, the world’s longest-serving motor sport prize? It’s only warranted a small mention in the World Endurance Championship arena, but this grand old prize was awarded to the winner of the Silverstone 6 Hours.

In 112 years it’s been awarded at a sports car race 29 times, GT races 11 times, to races for Grand Prix cars three times and for touring cars 25 times. Perhaps Alan Gow and TOCA might like to use it for a non-championship touring car all-comers race as they did 20 years ago? Or maybe the thriving British GT series should take it on? Undoubtedly there will be a lobby for reinstating Britain’s round of Formula E and using it for this purpose… it’s the in thing to do these days, after all.

Perhaps the most pragmatic suggestion is to permanently base the TT at Goodwood, where the current tribute race for 1960s GT cars can be restored to full glory. After all, there are few events in Britain that attract a similar size of crowd, and the prestige of winning it is enormous amongst a group of drivers and owners who actually care about its heritage and history.

At present, the longest-standing prize in motor racing history, a trophy that unites C.S. Rolls, Tazio Nuvolari, Sir Stirling Moss and Alain Menu is rootless. Steps must be taken fast to ensure that this grand old prize remains fixed to the greatest motor sport occasion on the calendar, the most stylish, the most glamorous and the most relevant – because if we lose our sense of identity at this moment of crisis for motor sport in Britain then we might as well all pack up and go home.