Here’s an interesting little meander through time that takes us through the greater part of the past century – from the air war over the Western Front to Texan boogie rock.

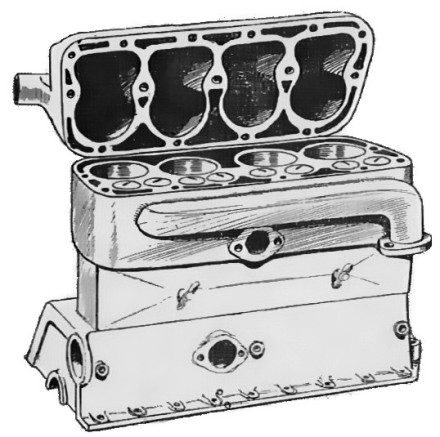

In the 1900s, the design and development of internal combustion engines became a French speciality and in their bid to increase reliability and profitability the Monobloc engine was created. Effectively this meant that far fewer individual components were needed if the the cylinder block, cylinder head and crankcase were all forged as a single item.

An early Monobloc design

Available as early as 1905 from manufacturers such as De Dion Bouton, the Monobloc truly came of age in the hands of Swiss designer Marc Birkigt, whose Hispano-Suiza V8 was lighter and more powerful than any other aero engine in the Allied arsenal… becoming effectively the Rolls-Royce Merlin of World War 1.

The Hispano-Suiza first found fame in the SPAD S.VII in which Capitaine Georges Guynemer briefly became the most successful Allied air ‘ace’ of the war, then became the power plant for Britain’s S.E.5 – arguably the greatest fighter design of the war. When the Americans arrived, they opted for the later SPAD S.XIII as their front-line fighter and in these machines were written the legends of Eddie Rickenbacker, Frank Luke and Raoul Lufbery, among others.

Eddie Rickenbacker’s patriotic SPAD – beautifully captured by Jim Dietz

As with all Monoblocs, even the Hispano-Suizas encountered some problems along the way. Primarily this was down to the outsourced manufacturing quality of components rather than the fundamental engine design – although most failures would serve to highlight any inherent weakness around the gasket and exhaust.

Nevertheless, the sophistication and power of the V8, together with the enthusiasm for ‘ace’ pilots in SPADs, set America thinking. If it could use its industrial might to iron out any kinks, then V8 power could become central to postwar living.

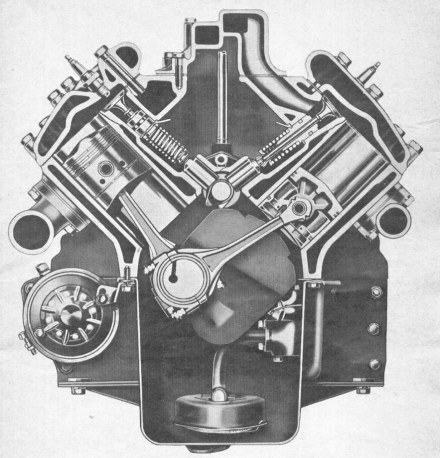

The most effective solution to the Monobloc‘s problems was to adopt side-valve design, reducing the stresses on the weakest links in the chain. It was with the side-valve ‘Flathead V-8’ engine that Ford Motor Company took the motoring world by storm between the wars.

Having established the mass production of motor cars with the Model T of 1908, Ford was content to rest on its laurels for 18 years until the advances in engineering that emerged from World War 1 finally caught up with the old ‘Tin Lizzie’.

Ford’s belated response was the Model A, which was barely less Spartan in its simplicity than the Model T but was packaged far more elegantly and, unlike its predecessor, featured controls in the same layout as most other mass-market cars.

The Model A Ford brought modern motoring to the masses

The Model A was a success, averaging almost a million sales per year, but the car buying market was growing ever-more sophisticated and demanding. Rivals such as General Motors were keen to offer an ever-increasing range of options based as much upon personalisation and comfort as they were to efficiency, while in Europe levels of style and sophistication were reaching their zenith.

Ford decided to try and outdo both.

The result was really only a single solution that went under many names, but for the sake of brevity it shall be called the 1932 Model B. As many major components as possible were carried over from the Model A but alongside the traditional 4-cylinder engine but alongside it in the showrooms was something rather special: a Monobloc V8 called the Model 18.

Ford’s version of the Monobloc V-8: the side-valve ‘Flathead V-8’

This was a Model B fitted with what Ford called its ‘Flathead V-8’. At a stroke, the Blue Oval could offer a smoother-running, more powerful engine for just $10 more than the standard 4-cylinder model. In total the Model B was also available with an array of 14 body styles, from standard sedans through roadsters, coupés, woodies and trucks… the very model of platform-sharing diversity.

The Model B and Ford’s Flathead V-8 became motoring icons overnight – and remained that way for decades. They were cheap to buy, relatively cheap to maintain and sold at a rate in excess of 300,000 units per year.

In 1933 the Model B was reworked again. As Ford’s motor won a following, so the car that it belonged to was given a longer wheelbase, a radiator grille shaped like a medieval knight’s shield and smoothed out styling on the inside and out. The Flathead V-8 was also tweaked; gaining better ignition to boost power. This would become the Model C, with the Flathead V-8 version being named the Model 40.

The 1933 Ford put a stylish face on a wide array of bodies

The V8 took hold among all American automobile manufacturers thereafter, but thanks to its low cost and endless variety of cars, Ford produced arguably the greatest icon of American motoring between the wars.

Not only that, but there were now European Ford V8s being built in England and Germany, led by the Ford V-8 Pilot. It was a boon to moonshine runners during prohibition, and in this era of Jimmy Cagney and Humphrey Bogart, the whole world fell under the spell of these smooth American engines.

During World War 2, V12s were the weapon of choice in the air but in the late 1940s, Ford’s faithful Flathead V-8 was still a mainstay of post-war motoring. It became the focus of a cottage industry of tuners and tweaks – either those who wanted to race on the drag strip and stock car circuit or continue to keep one step ahead of the law.

The birth of the hot rod movement and the NASCAR stock car racing series ensured that Flathead V-8s remained at the forefront. Kids bought them, stripped them, tuned them and had a whale of a time in their Little Deuce Coupes and a whole host of other variations on the theme.

The Beach Boys had their ’32 Ford – the Little Deuce Coupe

But then in the mid-Fifties, General Motors went and moved the goalposts with its ‘small block’ V8. This was a relatively fuel-efficient 90-degree V8 with overhead valves and pushrod valve train that would set new standards for light weight, compact size, general simplicity and remarkable durability.

After 40 years, the V8 Monobloc was history.

Chevrolet’s V8 became – and largely remains – the weapon of choice for America’s hot rodders and racers, who called it the Mighty Mouse for its ability to punch above its weight in the tuning shop – and colloquially the Mouse ever after. And among the legions of fans that the Mouse has won over the years was a man called Billy Gibbons, who is also among the world’s finest blues guitarists and one third of the boogie-rock band ZZ Top.

In 1976, Gibbons went to Don Thelen of Buffalo Motor Cars and Ronnie Jones of Hand Crafted Metal. The guitarist wanted to create the ultimate hot rod with the iconic looks of the 1933 Ford Model C and the refined power of a small block Chevy. It would take seven years to realise that dream – and the result was the legendary ZZ Top Eliminator.

Billy Gibbons (centre), with Frank Beard (thank you Matthew Carter!) and Dusty Hill – ZZ Top

While the car was being completed, Gibbons just happened to be in the process of turning ZZ Top’s brand of gnarly Texan blues-rock into a powerhouse of radio-friendly unit shifters. ZZ Top created an album that was to become as much a part of the Eighties cultural experience as Tom Cruise, big hair and shoulder pads… and it too was called Eliminator.

The completed car became the basis for the album’s artwork. It also starred in all of the videos for the hit singles that it spawned – Gimme All Your Lovin, Sharp Dressed Man and Legs. In fact the car provided the story in all the videos, in which young men were rescued from Cinderella-style drudgery by a bevy of beautiful women, who scooped them up and carried them off in the Eliminator to a world of good times, cheap sunglasses and bearded blues-rock.

Nice!

Now, there are few elements of the American Dream that are as instantly recognisable as the burble of a V8 engine. It’s a 90-year love affair that shows no sign of slowing down, for all the Elon Musks of the world. So just remember, next time you see a Hot Rod or watch a NASCAR race – or when your favourite TV cop arrives at a crime scene in a jet black Escalade – it’s as all-American as escargots de Bourgogne, fine champagne and fresh fougasse. Indeed, as all-American as the Statue of Liberty itself.

Vive les États-Unis d’Amérique!