Continuing the S&G’s odyssey through British achievements in motor racing, we come to the crowded era in between the two world wars, when the men and women of the Empire went motoring with aplomb. As with Part 1, this is not intended to be a definitive history, simply a glimpse of the major landmarks along the way.

1919

- The Cyclecar Club changes its name to the Junior Car Club and begins preparing for the restoration of racing at Brooklands.

1920

- Brooklands hosts its first motor racing event after extensive repair work is completed, following its wartime role as a primary hub for the British aviation industry. Among the day’s winners is Woolf Barnato, on a Calthorpe. Six more events are held in a season going through to October.

- Kenelm Bartlett wins the 350cc class at the first French Motorcycle Grand Prix, held at Le Mans, riding a Verus.

- The first Isle of Man TT since the war sees Tommy de la Hay win the Senior race on a Norton and Cyril Williams claim the Junior race for AJS.

- Shell’s wartime research into petrol properties by Harry Ricardo brings about the first fuels with different octane ratings.

Brooklands was restored to action and drew bumper crowds through the ‘Golden Era’

1921

- Brooklands hosts the first long-distance race to be held in Britain after World War 1, the 200 Miles Race, which is won by Henry Segrave on a Talbot-Darracq.

- Count Louis Zborowski reveals Chitty-Bang-Bang, the purpose-built racing car powered by a 23-litre Maybach Zeppelin engine and intended to take and hold the Brooklands Outer Circuit record.

1922

- Sunbeam wins the RAC Tourist Trophy – the first major international event staged in Britain since the end of World War 1 – with Jean Chassagne becoming the first foreign winner of the race.

- Stanley Woods wins the Junior TT for Cotton at the age of 18.

- D.J. Gibson becomes the first fatality among competitors at Brooklands since the end of World War 1.

1923

- Sunbeam finishes first and second in the French Grand Prix, with Henry Segrave taking victory.

- Garage proprietor Jack Dunn enters a Bentley in the inaugural Grand Prix d’Endurance – the Le Mans 24 Hours race.

- Dario Resta is killed attempting to set a speed record over a distance of 500 miles at Brooklands on a Sunbeam, when the buckle of a restraining belt works loose and causes a puncture. Resta’s riding mechanic Bill Perkins survives but is replaced for the forthcoming San Sebastian Grand Prix by Tom Barrett, who is killed when Kenelm Lee Guiness loses control. As a result of this accident, moves begin to ensure that riding mechanics are no longer carried in Grands Prix.

- Brooklands hosts the first dedicated Ladies’ Race, won by Mrs. O.S. Menzies on a Peugeot.

1924

- Jimmie Simpson wins the inaugural FICM European Motorcycle Championship 350cc class for AJS.

- Brooklands employee Charles Geary makes headlines when he murders his wife and attempts to take his own life.

- Motor Sport magazine is founded as a monthly dedicated to performance motoring and motor sport.

- The inaugural Lewes Speed Trials are held, and continue through the summer months each year until 1939.

- Jack Dunn takes a works-supported Bentley across the Channel to Le Mans, where he defeats an armada of French machinery to win the second running of the Grand Prix d’Endurance, sharing the car with Frank Clement.

- Malcolm Campbell raises the Land Speed Record to 146.16 mph in his Sunbeam Blue Bird at Pendine Sands.

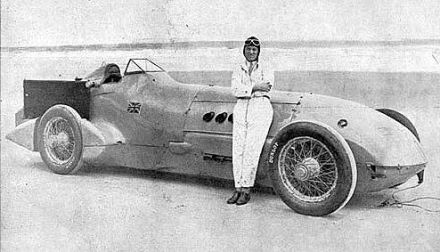

Malcolm Campbell was a hero to millions

1925

- After competing in the Monte Carlo Rally, the Hon. Victor Bruce wins the Mont des Mules hillclimb in his AC.

- The Aston Hillclimb at Kop Hill in Buckinghamshire sees a spectator injured when a car loses control. As a result, the Royal Automobile Club refuses to issue any further permits for speed events on a public highway. Only the Isle of Man and Ulster are exempt.

- Malcolm Campbell raises the Land Speed Record to 150.87 mph in his Sunbeam Blue Bird at Pendine Sands.

- Jock Porter wins the FICM European Motorcycle Championship 250cc class for New Gerrard.

- Local residents near Brooklands take legal action against noise from the race track, resulting in increased muffling of exhausts and other details of settlement.

- Wal Handley becomes the first rider to win two Isle of Man TT classes in a week – the Junior and the Ultra-Lightweight categories

1926

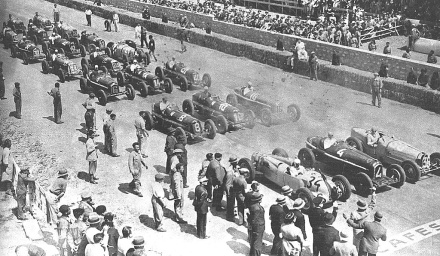

- Brooklands hosts the inaugural RAC Grand Prix, deciding round of the AIACR Grand Prix World Championship. Victory in the race – and the championship – is taken by Delage.

- British motorcycles and riders make a clean sweep of FICM European Championship titles, with Jimmie Simpson claiming the 500cc title (AJS), Frank Longman the 350cc (AJS) and Jock Porter the 250cc (New Gerrard).

- The Hon. Victor Bruce becomes the first British winner on the Monte Carlo Rally, sharing an AC with W. J. Brunell.

- John Parry Thomas raises the Land Speed Record to 170 mph in his Liberty-engined special called Babs at Pendine Sands.

- A cycling race is held on the land that will become Brands Hatch.

Delages dominated the first to Grands Prix in England

1927

- Crystal Palace circuit opens for motorcycle racing on a 1-mile loop of gravel and paved roads within Crystal Palace Park.

- British riders and motorcycles once again dominate the FICM European Championships with Graham Walker winning the 500cc title (Sunbeam), Jimmie Simpson the 350cc title (AJS) and Cecil Ashby the 250cc (OK-Supreme).

- Bentley takes its second victory in the Le Mans 24 Hours, driven by Dr. Dudley Benjafield and ‘Sammy’ Davies.

- Brooklands hosts its second and final RAC Grand Prix, won by Delage and confirming its successful defence of the titles won in 1926. Due to the increasing cost of the 1.5-litre supercharged Grand Prix formula, it is abandoned, along with the world championship, when the only other manufacturer entrant, Talbot, withdraws.

- After Malcolm Campbell sets a new Land Speed Record of 174.88 mph at Pendine Sands on the new Napier-Campbell Blue Bird. John Parry-Thomas is killed in Babs trying to win back the record, but Campbell is beaten the following month by Henry Segrave in the 1,000 hp Sunbeam Mystery, who reaches 203.79 mph at Daytona Beach.

- Wal Handley wins the Lightweight TT.

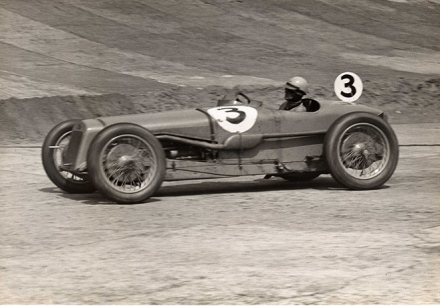

Twice European Motorcycle Champion, Graham Walker, in action

1928

- Malcolm Campbell sets a new Land Speed Record of 206.956 mph on his Napier-Campbell Blue Bird special on Daytona Beach.

- Wal Handley dominates the 500cc and 350cc FICM European Motorcycle Championship standings, riding for the Swiss manufacturer Motosacoche. Cecil Ashby claims the 250cc title for OK-Supreme.

- Bentley wins its third Le Mans 24 Hours, driven by Woolf Barnato and Bernard Rubin.

- The British Racing Drivers’ Club (BRDC) is founded by Dr. Dudley Benjafield, primarily as a social organisation.

- Kaye Don wins the first RAC Tourist Trophy for five years and the first to be held on the new Ards circuit formed of closed roads between Newtownards, Comber and Dundonald in County Down.

1929

- Henry Segrave raises the Land Speed Record to 231.446 mph in the Golden Arrow on Daytona Beach.

- More success for Britain in the FICM European Motorcycle Championship, with Tim Hunt winning the 500cc class for Norton, Leo Davenport claiming the 350cc title for AJS and Frank Longman the 250cc title for OK-Supreme.

- Bentley wins its fourth Le Mans 24 Hours, driven by Woolf Barnato and Sir Henry ‘Tim’ Birkin. The BRDC becomes active in organising races.

- Rudolf Caracciola wins the RAC Tourist Trophy at Ards on the Porsche-designed Mercedes-Benz SSK, the first foreign combination to win the race.

1930

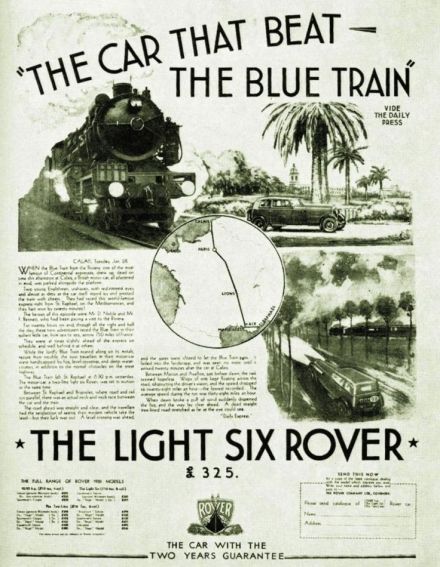

- Rover initiates the ‘Blue Train Races’ – namely trying to beat the luxurious Train Bleu which carried wealthy British passengers from the port at Calais to holiday destinations the Côte d’Azur. Driving south-to-north from a starting point in St. Raphael in January 1930, the Rover Light Six driven by Dudley Noble won by 20 minutes at an average of 38mph.

- Alvis beats le Train Bleu from St. Raphael to Calais by three hours with a Silver Eagle model driven by E.J.P. Eugster.

- Henry Segrave becomes the first British holder of the Water Speed Record, piloting Miss England II to 98.760 mph on Lake Windermere. He is killed attempting to improve on this speed later in the day, as was chief engineer Victor Halliwell.

- Woolf Barnato bets that he can not only beat le Train Bleu to Calais, but that he can be in his London club by the time that the train reaches the port. Barnato achieved the feat, arriving at his club four minutes before le Train Bleu stopped in Calais, but after using his victory to publicise the Bentley marque he is fined heavily by French police for abusing speed limits and dangerous driving, plus Bentley is banned from the Paris Auto Salon. The Blue Train Races are henceforth outlawed.

- Bentley wins its fifth and final Le Mans 24 Hours, driven by Woolf Barnato and Glen Kidston, defeating the supercharged Mercedes-Benz team after ‘Tim’ Birkin’s ‘Blower’ Bentley is used as a hare to draw the Germans on too fast. The winning car is then driven to Montlhèry for a 24-hour speed record attempt, but catches fire.

- Talbot takes the first class win at Le Mans for a British team, winning the 3.0-litre category. British pairing Lord Howe and Leslie Callingham win the 2.0-litre class on an Alfa Romeo and Lea-Francis wins the 1.5-litre class driven by Kenneth Peacock and Sammy Newsome.

- The first high-octane fuels are put on sale: Shell Racing is advertised for supercharged and high compression engines (sold as Shell Dynamin internationally).

- Rudge riders win two FICM European Motorcycle Championship titles – Irishman Henry Tyrell-Smith the 500cc class and Ernie not the 350cc class. Syd Crabtree wins the 250cc class for Excelsior.

- Tazio Nuvolari wins the RAC Tourist Trophy at Ards on an Alfa Romeo 1750 GS.

1931

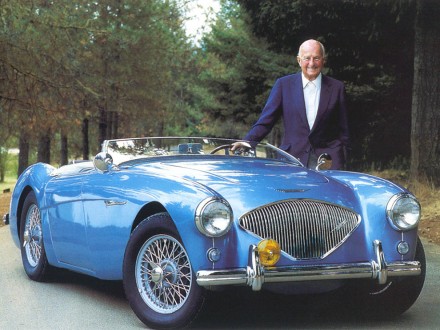

- Donald Healey becomes the first British winner of the Monte Carlo Rally at the wheel of an Invicta. He follows up this success with victory in the Coupe des Alpes.

- Malcolm Campbell reaches 250mph and sets a record of 246.09mph in his 1400hp Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird at Verenukpan in South Africa. He is knighted for his achievement

- George Eyston sets a new speed record for 750cc cars with 103.13 mph from EX120, an MG featuring his self-designed Powerplus superchager, at Montlhèry. He continues to set a new record of 101mph over an hour but on the final ‘insurance’ lap a fuel pipe breaks loose and the car catches fire, Eyston choosing to jump from the inferno at 60mph in his patented asbestos suit.

- Kaye Don takes the rebuilt Miss England II to South America, reaching 103.49 mph on the Paraná River to reclaim the Water Speed Record from America’s Gar Wood, in a fierce competition between the two men.

- The inaugural Ulster Motor Rally is held over a 1,000-mile distance from various starting points in Ireland.

- For the first and only time, British bikes and riders claim all four FICM European Motorcycle Championship titles, with Tim Hunt winning the 500cc for Norton, Ernie Nott the 350cc for Rudge, Graham Walker the 250cc for Excelsior and Eric Fernihough the 175cc for Excelsior.

- Fred Craner and the Derby & District Motor Club commence motorcycle racing at Donington Park.

- Earl Howe and ‘Tim’ Birkin win the Le Mans 24 Hours in an Alfa Romeo 8C, with Aston Martin winning the 1.5-litre class.

- Gwenda Stewart raises the 100-mile and 200km to 121mph at Montlhèry in the ‘Flying Clog’.

- Norman Black restores British pride by winning the RAC Tourist Trophy at Ards on an MG C-type Midget.

- George Eyston raises the 750cc record to 114mph in MG EX127.

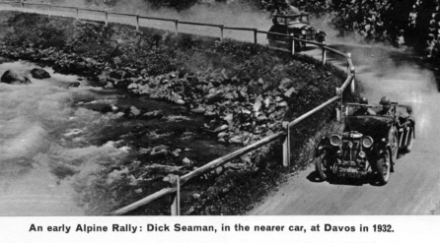

1932

- Sir Malcolm Campbell raises the Land Speed Record to 253.97 mph in the Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird at Daytona Beach.

- Kaye Don takes the Water Speed Record to 119.81 mph on Loch Lomond in the redesigned Miss England III.

- British entries sweep the Mont des Mules hillclimb at the end of the Monte Carlo Rally: J.W. Wright winning the 750cc class for MG, C.R. Whitcroft winning the 1.1-litre class for Riley, N. Black winning the 1.5-litre class for MG, T.C. Mann winning the 2-litre class for Lagonda, H. Widengren winning the 3-litre class for Alvis and Donald Healey winning the 5-litre class for Invicta.

- ‘Tim’ Birkin raises the Outer Circuit speed record at Brooklands to nearly 138 mph with his supercharged Bentley 4.5 litre but is scathing about the venue, saying: “I think that it is, without exception, the most out-of-date, inadequate and dangerous track in the world. Brooklands was built for speeds no greater than 120 mph and for anyone to go over 130 without knowing the track better than his own self is to court disaster. The surface is abominable. There are bumps which jolt the driver up and down in his seat and make the car leave the road and travel through the air.”

- F. Dennison wins the inaugural Scottish Rally in a Riley.

- Donald Healey and the Invicta triumph on the Coupe Internationale des Alpes, co-driven by Ian Fleming. The Hon. Brian Lewis takes class honours in a Talbot.

- Cyril Whitcroft wins the RAC Tourist Trophy on a Riley Brooklands Nine.

- Norton retains the 500cc class of the FICM European Motorcycle Championship, ridden by Italian star Piero Taruffi.

- The first grasstrack motorcycle race is held at Brands Hatch.

- Aston Martin maintains British honour at Le Mans with a second successive 1.5-litre class win.

- The inaugural Royal Automobile Club Rally sees 367 cars entered for the drive a 1,000-mile route to Torquay starting from nine different towns and cities (London, Bath, Norwich, Leamington, Buxton, Harrogate, Liverpool, Newcastle upon Tyne and Edinburgh). It is won by Col. Loughborough in a Lanchester.

1933

- Sir Malcolm Campbell raises the Land Speed Record to 272.46 mph in his revised 2300hp Rolls-Royce engined Blue Bird at Daytona Beach.

- Jimmie Simpson wins the FICM European Motorcycle Championship at 350cc for Norton, Charlie Dodson wins the 250cc class for New Imperial.

- British winners on the Coupe Internationale des Alpes include Harold Aldington’s Frazer Nash overall, with Riley and MG taking class honours.

- Kitty Brunell wins the JCC Brooklands Rally in an AC.

- MG becomes the first non-Italian manufacturer to win class honours on the Mille Miglia with its K3 Magnette, driven by George Eyston and Count Lurani

- British cars dominate the slam capacity classes at Le Mans: Riley wins the 1.1-litre class and finishes fourth overall, followed by the 1.5-litre class-winning Aston Martin and the 750cc winning MG.

- C. Griffiths wins the Scottish Rally in a Riley.

- K. Milthorpe wins the Scarborough Rally in a Wolseley Hornet

- Stanley Orr wins the Ulster Rally in an Austin 7.

- ‘Tim’ Birkin dies as a result of septicaemia incurred from a burn to his arm while racing in the Tripoli Grand Prix.

- Tazio Nuvolari returns to the RAC Tourist Trophy, taking victory for MG in the same car that won its class on the Mille Miglia

- Kitty Brunell becomes the first British woman to win a major motor sport event when she claims the RAC Rally in an AC Ace

- English Racing Automobiles (ERA) is founded by Raymond Mays and Peter Berthon with funding from Humphrey Cook, producing single-seat Voiturette cars with a Reid Railton-designed chassis and bodywork by George and Jack Gray, with the engine and transmission based around Mays’ supercharged 1500cc Riley.

1934

- Donald Healey finishes third overall on the Monte Carlo Rally in a Triumph Gloria

- Cadwell Park circuit begins holding motorcycle races.

- Bo’ness Hillclimb hosts its first event.

- Triumph takes class victory on the Coupe Internationale des Alpes.

- Charlie Dodson wins the RAC Tourist Trophy for MG

- Jimmie Simpson retains his 350cc FICM European Motorcycle Championship title with Norton.

- Raymond Mays sets Class F speed records in ERA R1A at Brooklands, achieving 96.08mph for a mile from a standing start.

- Riley wins the 1.5 litre class at Le Mans and finishes second overall; MG wins the 1.1-litre category.

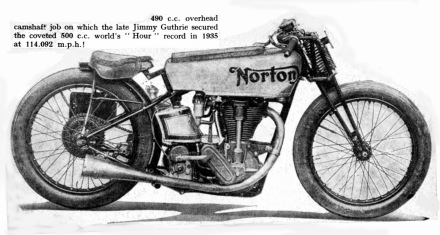

- Jimmie Simpson wins the Lightweight 250cc category on the Isle of Man TT, his first class win in 12 years of trying. Jimmie Guthrie beats Simpson to win both the Senior and Junior TT for Norton.

- R.G. Spikins wins the RAC Rally in a Singer Le Mans

- A battle between Mrs. Kay Petre and Mrs. Gwenda Stewart for the women’s Outer Circuit lap record at Brooklands sees speeds increase over three days to reach 135.95 mph in Gwenda Hawkes’ favour.

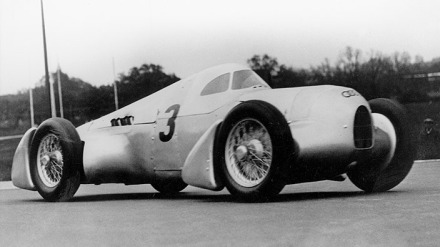

English Racing Automobiles would dominate Voiturette racing

1935

- C. Ridley finishes second overall on the Monte Carlo Rally in a Triumph Gloria.

- Sir Malcolm Campbell raises the Land Speed Record to 276.816 mph in the Blue Bird at Daytona Beach, but is convinced that he can go faster on a better surface. Six months later on the Bonneville Salt Flats he achieves 301.129 mph.

- George Eyston sets a 24-hour speed record of 140.52 mph in the Rolls-Royce V12-engined record car Speed of the Wind on on the Bonneville Salt Flats.

- Lagonda becomes the second British marque to take overall victory at Le Mans. Aston Martin wins the 1.5-litre class and MG triumphs in the 1.1-litre category. The 750cc class is won by Austin.

- Jimmie Guthrie wins the 500cc FICM European Motorcycle Championship for Norton, Wal Handley claims the 350cc class for Velocette.

- Fred Craner of the Derby & District Motor Club holds the inaugural Donington Grand Prix, won by Richard ‘Mad Jack’ Shuttleworth on an ex-Scuderia Ferrari Alfa Romeo P3.

- John Cobb sets the all-time Outer Circuit record at Brooklands, at a speed of 143.44mph. An observer states: “On the Byfleet the Napier-Railton seemed to be in a steady slide, the tail a little higher on the banking than the front”

- In a year of success for ERA, Raymond Mays wins the Voiturette race at the German Grand Prix in R3A as the first international racing success for the type. Pat Fairfield then wins the Manin Beg, Nuffield Trophy and Dieppe Voiturette Grand Prix at the wheel of R4A, while Dick Seaman wins the Coppa Acerbo Junior, Swiss Voiturette Grand Prix, and Masaryk Voiturette Grand Prix in Czechoslovakia in R1B

- Freddie Dixon wins the RAC Tourist Trophy for Riley

- Amid a plethora of class wins on the RAC Rally’s 1000-mile routes to Eastbourne, no overall winner is declared

1936

- Dick Seaman is insuperable in 1.5 litre Voiturette racing, using a 10-year-old Delage Grand Prix car rebuilt to modern standards by ex-Alfa Romeo and Scuderia Ferrari engineer Giulio Ramponi (see picture at the top of this article).

- ERA continues to win despite Seaman’s defection – B. Bira wins Voiturette races at Monaco, Picardy and Brooklands in R2B Romulus, and at Albi in R5B Remus; Reggie Tongue won the Ulster 200 as well as hillclimb wins in Germany, Switzerland and Shelsley Walsh in R11B Humphrey and numerous other minor events were won. However, Marcel Lehoux was killed in R3B rolled and caught fire at Deauville.

- George Eyston reclaims the 24-hour speed record from America’s Ab Jenkins, averaging 149.096 mph in Speed of the Wind at Bonneville. He continues to set a 48-hour record of 136.34 mph.

- Jimmie Guthrie wins his second straight 500cc title in the FICM European Motorcycle Championship, and Freddie Frith wins the 350cc title, both riding for Norton.

- John Cobb beats Eyston’s 24-hour speed record at Bonneville, averaging 150.163 mph in the Napier-Railton.

- Tommy Wisdom wins the Coupe Internationale des Alpes in an SS 100 Jaguar.

- Seaman and Hans Reusch win the second Donington Grand Prix on an ex-Scuderia Ferrari Alfa Romeo 8C/35

- Crystal Palace circuit is extended to a 2-mile length and fully paved to allow car and motorcycle racing to take place.

- Freddie Dixon and Charlie Dodson share victory in the RAC Tourist Trophy for Riley, although the race is marred when Jack Chambers in another Riley loses control and crashes into the crowd killing 8 spectators and injuring 40 others, 18 of them seriously. The Ards circuit is abandoned and the 1937 Tourist Trophy is moved to Donington Park.

- E.A. Westacott wins the RAC Rally in an Austin 7

1937

- Dick Seaman joins the Mercedes-Benz Grand Prix team

- Bira becomes the winner of the inaugural London Grand Prix on Crystal Palace circuit in ERA R12B Hanuman.

- Aston Martin wins the 1.5-litre class at Le Mans

- Jimmie Guthrie wins both the 500cc and 350cc FICM European Motorcycle Championship titles, which are awarded posthumously after he is killed attempting to complete a hat-trick of wins in the German Motorcycle Grand Prix senior race.

- The ERAs keep winning in Voiturette competition, Charlie Martin claiming at the German Grand Prix meeting in R3A, Pat Fairfield taking three wins in South African races with R4A, Raymond Mays winning the Picardy Grand Prix in R4C and Peter Whitehead victorious in the Australian Grand Prix in R10B.

- Armed with Blue Bird K3, a new hydroplane designed by Fred Cooper of Saunders Roe and powered by a Rolls-Royce R aero engine, Sir Malcolm Campbell raises the Water Speed Record to 129.50 mph on Lake Maggiore.

- Rising star Tony Rolt wins the Coronation Trophy race at Brooklands in a Triumph Dolomite.

- Freddie Frith becomes the first man to average 90mph around the Isle of Man Mountain Circuit, riding a Norton

- The mighty Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz teams dominate the third Donington Grand Prix, drawing a crowd of 60,000.

- George Eyston sets a new Land Speed Record of 311.42 mph in Thunderbolt at Bonneville.

- Franco Comotti wins the RAC Tourist Trophy at Donington Park on a Talbot-Lago.

- Jack Harrop wins the RAC Rally in an SS 100 Jaguar.

1938

- Prescott holds its first hillclimb.

- ERA reveals the new E-Type Voiturette, designed after the style of the Mercedes-Benz grand prix cars with an offset driveshaft lowering the car’s profile and centre of gravity.

- Ted Mellors becomes the last British rider to win honours in the FICM European Motorcycle Championship, taking the 350cc class for Velocette, as the rise of German machines and riders swamps the major classes.

- Dick Seaman wins the German Grand Prix for Mercedes-Benz.

- George Eyston and John Cobb battle for the Land Speed Record at Bonneville, with three records set – Eyston ending as the fastest man at 357.5 mph in Thunderbolt, after Cobb’s best effort of 350.2 mph in his Railton Special set an interim record.

- British driver A.F.P. Fane wins the 2.0-litre class on the Mille Miglia for BMW

- Sir Malcolm Campbell’s Blue Bird K3 reaches a new Water Speed Record of 130.91 mph on the Swiss Halwillersee.

- Despite a pause caused by the Munich Crisis, Tazio Nuvolari claims victory in the fourth and final Donington Grand Prix, watched by a young Murray Walker, son of former motorcycle champion Graham and future commentating superstar, among the crowd of 65,000.

- Louis Gérard wins the last pre-war RAC Tourist Trophy on a Delage D6.

- Jack Harrop becomes the first double winner of the RAC Rally in his Jaguar SS100.

1939

- John Cobb returns to Bonneville with his Railton Special to set a new Land Speed Record of 369.74 mph.

- After a lean year in 1938, the Brits bounce back at the final pre-war Le Mans 24 Hours; Walter Watney’s team finishing second overall and first in the 3.0-litre class with a Delage in front of the 5.0-litre class winning Lagonda V12 in third overall.

- A.F.P. Fane wins the RAC Rally for BMW, the first foreign make to take victory on the event.

- Georg ‘Schorsch’ Meier becomes the first overseas winner of the Senior TT, riding a supercharged 500cc BMW.

- Dick Seaman crashes out of the lead of the Belgian Grand Prix, dying the following morning from his injuries.

- Tony Rolt buys ERA R5B Remus from Prince Bira and Prince Chula, which catches fire in its first event at Brooklands – Rolt puts his gloved hand over a hole in the firewall and wins the race, well ablaze. He serves in the Rifle Brigade during the early months of World War 2, being captured in the defence of Calais in 1940 and attempting to escape seven times in the next four years.

- Using the new Vespers-Built Blue Bird K4, Sir Malcolm Campbell raises the Water Speed Record to 141.74 mph on Coniston Water.

- Just four weeks before the outbreak of World War 2, Brooklands hosts its last ever race meeting. It becomes a centre for wartime aeronautical research and aircraft production, with Barnes Wallis establishing his office in the Clubhouse from which the Upkeep Dam-Buster bomb, Tallboy 6-tonne and Grand Slam 10-tonne earthquake bombs are produced. German bombing raids, increased aircraft production and general wear-and-tear will put the track out of service forever

- A.F.P. Fane signs a contract to replace Dick Seaman at Mercedes-Benz, which is unfulfilled. During World War 2, Fane flies the reconnaissance missions in a Spitfire that reveal the location of the battleship Tirpitz in Norway, leading to her destruction by Lancasters from 617 Squadron. After flying 25 PR operations with 1PRU (17 successful) – and a total of 98h 50m operational time – Fane is killed attempting to follow the railway lines back to RAF Benson while flying in thick fog.

A still from Andy Lambert’s brilliant aerial film of Brooklands today