‘They have the most astonishing audacity in some parts of Europe. For instance, there is going to be a Grand Prix at Monaco – a Grand Prix, mark you, in a Principality which does not possess a single open road of any length, but has only ledges on the face of a cliff and the ordinary main thoroughfares that everyone who has been to the Casino knows so well…”

The Monaco circuit in its earliest form

So reported The Autocar magazine early in 1929, after the founding father of the Monaco Grand Prix, Antony Noghes, defied both convention and the disbelief of the AIACR – fore-runner to the FIA – in order to stage a motor race.

It was the previous year when Noghes, the president of the Automobile Club de Monaco, decided that top-flight motor racing was an essential addition to the prestige of the Principality if it were to hold its head high in Europe. Regional grands prix were being held in nearby Cannes and Nice, and just a few miles away lay the celebrated La Turbie hillclimb – and Noghes was determined that the Monegasques should not be overlooked.

The Automobile Club de Monaco had grown from the Cycling and Automobile Club of Monte Carlo, which itself had founded the Monte Carlo Rally some 17 years earlier. This celebrated run to the Riviera from all points of the compass was one thing, but clearly the sport’s governors thought that this grand prix idea was preposterous.

“Your rally is a large-scale event, we quite agree,” said the letter from the AIACR. “But you need the whole map of Europe for it… you cannot do anything in Monaco.”

Noghes was not a man to take ‘non’ for an answer

An indignant Noghes protested that Monte Carlo could and indeed would hold a grand prix – even if he himself had no idea where at the time. In a tremendous state of Gallic high dudgeon he wrote back to the AIACR stating that he could: “inform you, sirs, that next year you will be present at an international race which will be held on the territory of the Principality and which will excite world-wide interest.”

In the stunned silence that followed his reply, Noghes busied himself with driving around the whole of Monte Carlo in search of suitable roads – a search which time and again drew him back to the streets of the capital, Monaco.

“For days on end I went over the avenues of the Principality until I hit on the only possible circuit,” he recalled, almost 40 years later.

“This skirted the port, passing along the quay and the Boulevard Albert Premier, climbed the hill of Monte Carlo, then passed around the Place du Casino, took the downhill zig-zag near Monte Carlo station to get back to sea level and from there, along the Boulevard Louis II and the Tir aux Pigeons tunnel, the course came back to the port quayside.”

With his route fixed, Noghes presented this outline for a small but challenging street circuit to the great Monegasque racing driver Louis Chiron – who declared the course ‘stupendous’. It was also impossible to drive around at that time, because the route Noghes had worked out included the great stone steps next to the Bureau de Tabac which linked the Quai Etats Unis with the Quai Albert I.

The run to Tabac was the sticking point in Noghes’ design

Between them, Noghes and Chiron managed to generate sufficient interest among the hoteliers and stakeholders in the city that the track was indeed approved. The old stone steps were demolished in favour of a smooth incline – or, in other words, the heart of Monaco was reshaped for the race, under the approving eye of His Serene Highness Prince Peter. The race would be on.

A mildly incredulous AIACR duly sanctioned the inaugural Monaco Grand Prix to take place on April 14 1929. Their feelings were amply covered in the press leading up to the race, with The Motor declaring that “…there is no doubt that the course is exceedingly difficult and calls for a first-class car and a really expert driver…”

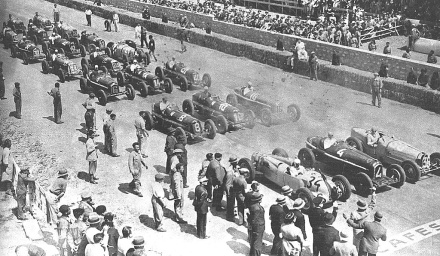

Although none of the 16 cars which arrived for the race had been built in England (the field numbering eight Bugattis, three Alfa Romeos, two Maseratis, a Corre-la-Licorne, a Delage and a Mercedes-Benz), the whole idea struck a chord with the madcap British motoring fraternity – as The Autocar attested:

“That capital little affair, the Monte Carlo Grand Prix, which is to run wild through the streets of the Principality, has received twenty-three entries, all of which the promoters appear anxious to start. This affair should be the nearest approach to a Roman chariot race that has been seen of recent years…”

‘Chariots’ at the ready for the first Monaco Grand Prix

If the Brits felt that the idea of tonking around the streets of Monaco was all rather jolly before the race then their ardour was only enflamed by a British winner – in the form of William Grover, racing under the name ‘W. Williams’.

Grover was not a member of the Brooklands fraternity – indeed he was half French, had lived virtually his whole life in France and was a member of the works Bugatti team. Yet while he was not a member of the coterie of Campbell, Segrave, Birkin et al the blue paint on his Type 35B – the only works car entered – was nevertheless over-painted in British racing green before the race. Certainly his victory was eagerly accepted as being 100% British among those back home…

The victory of ‘Williams’ was quickly claimed by the British

After 85 years the Monaco circuit still leaves people agape and chuckling with amazement at the idea of threading grand prix motor cars through its narrow, vertiginous streets. Its remarkable creator, Antony Noghes, lived long enough to see the likes of Nuvolari, Moss, Lauda and Prost earn their spurs on his circuit. Much has of course changed in the name of safety, commerce and outright greed but one suspects that the likes of Chiron and ‘Williams’ would recognize the event in a heartbeat – and be extremely proud of their ongoing legacy.