A lot is said and written about British leadership in motor sport. About its value. About its importance. We speak in terms intended to summon up the blood in a manner that would have delighted Henry V at Agincourt.

‘Twas not always thus. Brooklands may have been the world’s first permanent race track and a few pioneering marques such as Bentley, Napier and Sunbeam may have successfully raided the most prestigious races in Europe but, before World War 2, Britain was hardly smitten.

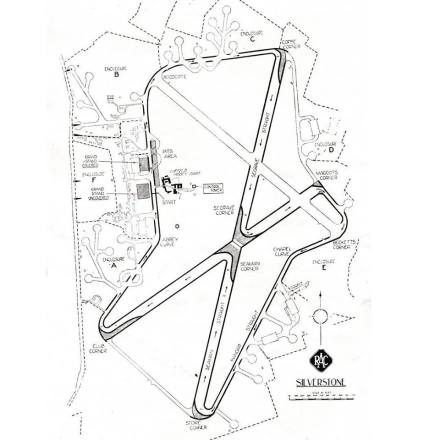

Racing cars not permitted: the SMMT shows its wares

Indeed, the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders was moved to prohibit the display of racing machinery within its annual Motor Show – stating that competition was ‘vulgar and irrelevant’.

All that was changed by the Second World War. In its wake a tide of bright young engineers and hard charging drivers was unleashed. That tide grew in depth, strength and experience until Britain became the motor racing capital of the world.

The year of British ascendance was 1956. If the primary measuring stick of motor sport is Formula One, then this was the first year when the number of British teams outnumbered those from Italy or France. It is also the first year in which British drivers won more grands prix than any other nationality – with Stirling Moss and Peter Collins claiming two victories apiece.

Young bucks Collins and Moss ran the old master Fangio (right) close in 1956

Of course this was also the year in which Collins famously missed out on the world championship after handing his car to his title rival and team-mate, Juan Manuel Fangio, in the final race of the year. Clearly the British still had to develop the killer instinct in these situations!

Neither Moss or Collins were driving British cars, but there was plenty of success outside Formula 1 for British manufacturers. Leading the way was Jaguar, which maintained its dominance at the Le Mans 24 Hours with a fourth victory in six years – with Aston Martin and Lotus winning class honours.

Jaguar’s fourth winner at Le Mans is crowned

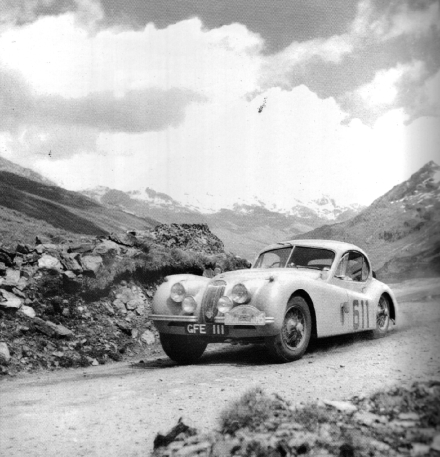

In rallying, Jaguar also the Monte Carlo Rally with its vast Mk.VII saloon and Aston Martin won the RAC Rally with its rather more obviously sporty DB2/4.

Meanwhile, back on the tracks, the Owen Maddock-designed Cooper T41 dominated in Formula 2, establishing the template for rear-engined simplicity that would carry the Kingston firm to world championship glory by the end of the decade.

Jaguar also claimed victory in the 1956 Monte Carlo Rally

If that wasn’t sufficient to set the seal on British dominance then Stirling Moss – that man again! – set new class speed records at Monza in a streamlined Lotus Eleven.

It was a year that would define so much for so many people: the year in which the remarkable community of engineers and adventurers showed exactly what they were capable of. The achievements of 1956 set in place the foundations for a huge and vibrant industry.

This week the great and the good of that same industry gather for their annual jamboree – the Autosport International show in Birmingham. Doubtless there will be much bullish talk about the state of the nation… but how much of it is justified?

One thing is clear – the age of British leadership in motor sport that arrived with such a tour de force in 1956 has, in fact, passed.

At the end of last year Britain lost 25% of its F1 production in the space of a fortnight. If a quarter of the Premier League teams vanished there would be rioting on the streets – but the disappearance of more than 400 jobs and hundreds of millions of pounds owing to suppliers has merited barely a raised eyebrow.

This misfortune is, however, just the tip of the iceberg. For example British Formula 3 – the series that was the making of virtually every F1 driver from Stirling Moss to Jenson Button, including the likes of Nelson Piquet, Ayrton Senna and Mika Häkkinen – has ceased to exist, after drawing only half a dozen entries in recent seasons.

The Le Mans 24 Hours and World Endurance Championship are currently contested by Audi, Porsche and Toyota… all based in Germany. Both of the full works teams entered in the World Rally Championship – Hyundai and Volkswagen – are also based in Germany.

In terms of manufacturing there are now only three viable options when it comes to single-seater chassis supply: Mygale from France (Formula Ford/Formula 4), Dallara (GP2, GP3, Formula 3, Indycar, World Series, Formula E) and its Italian compatriot Tatuus (Formula Renault).

Across virtually every discipline of the sport, from rallycross to hillclimbs and truck racing to dragsters, British influence is increasingly on the margins. As well as car production, traditional bastions of the industry such as Dunlop and Shell have also moved their motor sport arms (and associated Research & Development of customer products) away from Britain.

In 2001 the Motorsport Industry Association, the self-appointed lobbying group in the UK, valued the industry at £5bn a year – which was quite punchy. These days the MIA puts that figure at £10bn – which is frankly ludicrous.

In the years since 2001 such prestigious engineering firms as Cosworth, Reynard, Lola, Van Diemen, TWR and Ralliart have hurtled into oblivion. On the domestic front, the British Touring Car Championship lost its manufacturer entries and star drivers but has battled on – and at least survived where the British Rally Championship has been consigned to history.

One by one the lion’s teeth have been pulled.

What took Britain to the top of the world in 1956 and kept it there for roughly half a century was a fraternity imbued with talent and inventiveness as well as the willingness to challenge tradition. As a community we urgently need to revive this same spirit if we are to have any chance of halting the decline.

Britain needs to recapture the pioneering spirit it showed in 1956 – and fast

The S&G is a place to look backwards but, at the start of a new year, it might also be a good time to look forwards – and worry. Context is really what this blog is about, and if by looking back we can find a way to fan the embers then so much the better.

The Scarf and Goggles bar at the 2015 Silverstone Classic

The Scarf and Goggles bar at the 2015 Silverstone Classic