There is a whisper that Richard Petty has decided to call time on his popular appearances at the Goodwood Festival of Speed after one last triumphant visit this year. At 81 years of age, it’s understandable that the man who has signed more autographs than anyone else in history should decide to throttle back a bit – but by gum he’ll be missed on this side of the Pond.

His rangy figure, diamond white smile and trademark moustache have aged well beneath the ever-present STP-branded sunglasses and Charlie 1 Horse hat. Thoughts of ‘King’ Richard abdicating the throne still seem rather abstract, and in an age when certain US – ahem – dignitaries have done their worst, he is a reminder of the very best that the American Dream has ever had to offer.

“We were living in a three-room house on a dirt road with no electricity, no telephone… you know, no communications,” the King remembered recently of his childhood in New Cross, North Carolina.

“You didn’t know that there was another world out there! So you lived in your world and you was as happy as a June bug ‘cos you had as much as the guy next door… My mother and daddy, they were very stern, they had certain rules, you knew what the rules were and if you broke ‘em you got whopped!”

That daddy was of course the first real superstar of NASCAR racing: Lee Petty. The family may not have had much as Richard and his brother Maurice grew up in New Cross, but his father’s gift with internal combustion brought home the bacon.

During the prohibition era, nothing could help support a living scratched from the Carolina soil quite like running moonshine – at which Lee Petty’s tuning and driving skills put him in the top rank. As a side occupation, the bootleggers would race one another to see who had the fastest car, making serious money from the bets that were placed on these events.

After World War 2 the survivors of that generation of rowdy racers and tuners congregated under the NASCAR banner. They went at it on Daytona beach and other oval tracks across the south-east USA – and Lee Petty was one of the most successful drivers of his era, who backed up raw talent with a willingness to bend the fenders of his rivals in order to get ahead.

The elder Petty was a double champion and the most successful driver of NASCAR’s first decade. Meanwhile in 1956-57, you Richard took his first steps on the circuit… while brother Maurice learnt the dark arts of race tuning.

At the 1961 Daytona 500, the third running of the race on that mighty 2.5-mile banked oval, Richard Petty went over the Turn 1 barrier – fortunately without serious injury. His father, however, was pile-driven through the metal guardrail entering Turn 4 and suffered career-ending injuries. All emphasis went on the Petty boys’ careers, with father Lee presiding over the pit lane.

The King ascends: the 1964 Plymouth and Richard Petty

It was a partnership that flourished as the motor manufacturers began to take an interest in NASCAR to promote their products. The Pettys received support from Plymouth, and the cars painted in their unique shade of blue were absolutely dominant. Young Richard won his first NASCAR Grand National title in 1964 with 9 victories, including his first Daytona 500 win, to earn an unprecedented $114,000 in winnings alone – that’s close to a million dollars in today’s money. You could do a lot of things in New Cross with a million dollars even today.

Petty’s success was attributed to the Hemi engine, which was immediately banned. Thus Petty went to compete in drag racing for 1965 in protest at NASCAR’s decision. Unfortunately, an accident resulted in the death of a six-year-old boy and the injury of several bystanders, but his successes continued despite the tragedy.

The Hemi was reinstated for NASCAR use in 1966 and a total of six more championship titles would be added between 1967 and 1979 – in a wide variety of makes and models. Whether he was in a Plymouth, Ford, Dodge, Oldsmobile, Chevrolet, Buick or Pontiac, the King could be spotted in a heartbeat thanks to the family’s distinctive ‘Petty Blue’ paint, together (from 1971), with the fluorescent red of oil company STP.

A final total of 200 race wins was reached in a fever-pitch afternoon at Daytona in July 1984, when the delayed Ronald Reagan arrived in Air Force 1 in the middle of the race, becoming the first sitting president to attend a NASCAR event. Of course he witnessed what would turn out to be the King’s final race victory.

The King’s 200th and final win came, fittingly, at Daytona

The King remained firmly in the driving seat of his blue number 43 car until 1992. He wasn’t competitive but he remained the fans’ favourite. The compulsion to stay was understandable although it nearly claimed him several times – not least his wild crash at the 1988 Daytona 500. When he bowed out after 35 years in the cockpit, there was a celebration like few others.

It’s unlikely that anyone in stock car racing – or anywhere else in motor sport – will have a career as gilded as that of the King. Yet there was no guile to it all, as he once said: “I just tried to win every week and if the math worked out at the end they gave me a big trophy.”

Nobody can escape the occasional controversy in a career of 60-odd years and counting. Petty was instrumental in the banishment and shameful silence that surrounded the dying days of NASCAR wild child Tim Richmond in 1987-89, when he developed full-blown AIDS. The two men were worlds apart and Richmond, the free-wheeling rich kid from Ohio who would fly to New York for a haircut, raised the King’s hackles just for existing.

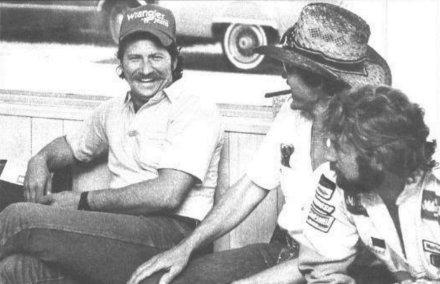

Dale Earnhardt, the King and Tim Richmond on the infield

Like all too many in the NASCAR firmament, the King wasn’t short of disparagement for Danica Patrick, either.

This latter point has some resonance at the S&G, where Danica was considered a friend during her early days in Britain and her pace, determination and willingness to bat prevailing sexism to the boundary were staggering. To the men of NASCAR, when one driver hits another on the rear quarter panel to put them in the wall, it’s considered an act of war. Fists fly and a race or two later the compliment is returned… but when it happened to Danica – and getting hit was the cause of most of her (admittedly many) NASCAR accidents – she was branded an ‘idiot’ every time.

When a woman driver eventually follows Danica’s lead and pushes on to Victory Lane, it will doubtless genuinely stun a man raised in the Bible Belt of the 1930s. Yet the King, to his enduring credit, is no caricatured Confederate. The family of NASCAR’s first black driver, Wendell Scott, remember that he would often find tyres, tools and even engines in his pit that had ‘accidentally’ been left there by the number 43 crew in what was otherwise a pretty unfriendly environment.

Today, Bubba Wallace is the first black driver with a full-time seat in NASCAR for more than a decade. He drives Richard Petty’s number 43.

The King and Bubba Wallace have revived the number 43’s fortunes in 2018

Not since Petty’s last great run of success in the 1970s has the number 43 been such a hot property, with a hugely popular driver taking results like second place in this year’s Daytona 500. After decades in the wilderness, Petty has regrouped and his business appears to be thriving once again – thus there’s an air of contentment and completion about the King which is richly deserved.

Since 2006 he has been part of the Festival of Speed experience. Initially he was slightly taken aback by the fervour that the Brits met him with, and put his popularity down to being the only guy in a cowboy hat at Lord March’s garden party.

Every time a different one of the treasures from his museum at The Petty Garage in New Cross has been fettled, primed and sent up the hill – although this year the King handed over driving duties, giving even more time for selfies and autographs. Goodwood will be all the poorer for his absence in future, but the S&G wishes the King many more good years, grateful that there is still a star of the 1950s who is still active in the sport to this day.

As testament to this remarkable man, here are some other lesser-known facts about Richard Petty:

- The outfit worn by Burt Reynolds in Smokey & The Bandit was designed around the kind of off-duty threads worn by the King in the mid-Seventies – who is also namechecked in the script. He’s still not averse to busting out a red shirt, either…

- Petty always refused sponsorship from alcohol brands, and never claimed cash awards that were sponsored by them, in deference to his mother’s wishes

- He raced with a broken neck. More than once.

- He’s signed in excess of 2 million autographs – having developed his bold, looping script for that purpose. In 2017, the King said: “Right early I looked in the deal and we had no sponsors at that time, and the purse didn’t come from the promoter; it came from the people sitting in the grandstand. So I said: OK, I’m gonna sign this, but when they get home I want them to be able to read who said ‘thank you’. Those are the people that put me in business and the reason why all (the media and sponsors) are here. If it wasn’t for the fans you’d probably have to go to work for a living!”

- Of his 200 wins, 30 were on dirt tracks before NASCAR got all fancy and only raced on asphalt

- He raced 307,836 laps on his way to those 200 wins, with 555 top-five finishes, 712 top-10 results and 123 pole positions

- At Texas in 2017 a caution was thrown when a stetson blew onto the track. From the 43 car run by Richard Petty Motorsports, driver Bubba Wallace cheekily radioed his pit to ask if the King needed assistance. His spotter immediately replied that there were two things Richard Petty didn’t lose often: races and hats

- Richard Petty and his wife Lynda provided the voices for the blue number 43 Plymouth Superbird and matching blue 1975 Chrysler Town & Country Station Wagon in the Disney/Pixar movie Cars

- In 1967 he won 27 out of 48 races entered

- He refuses to have any painkillers at the dentist as a reminder to take better care of his teeth

- He is a walking quote machine, with such lines as: ‘When was the first automobile race? The day they built the second automobile,’ and ‘I don’t know how many laps I led, all I know is that I led the last one 200 times.’

- He refers to people as ‘cats’ and habitually bids farewell with a shaka or ‘hang loose’ hand sign

- His first top-10 finish in NASCAR was recorded on July 26, 1958 and his last was 33 years and 16 days later

Ladies and gentlemen: the King!